Geology influences the characteristics that define a terroir. The topography, i.e. the relief and its morphology, depends on the type of rocks making up the subsurface and its structure. It is also the relief that partly influences the quality and diversity of the wines, depending on the exposure of the slopes.

Join us on a tour of France with five stages describing the geology of the great wine producing areas to show how geology affects the quality and properties of wines.

About the author

A doctor of geology, Nicolas Charles is a geologist at BRGM, the French Geological Survey. He is involved in numerous geological mapping and mineral resource projects in France and abroad. Since 2016 he has been coordinating a European geoscience training project in Africa (PanAfGeo) aimed at strengthening partnerships between European and African geological surveys. He is the author of numerous scientific outreach publications on the French geological heritage and also holds conferences on geology and mineral resources.

Sancerre, a symbiosis of geology and terroir

"Terroir”. This French word has become universal because it is used in most languages. Originally referring to the land of a village community, the word, which is at least six centuries old, has now been defined by the International Organisation of Vine and Wine: “Vitivinicultural terroir is a concept which refers to an area in which collective knowledge of the interactions between the identifiable physical and biological environment and applied vitivinicultural practices develops, providing distinctive characteristics for the products originating from this area.

Terroir includes specific soil, topography, climate, landscape characteristics and biodiversity features.”

In other words, the notion of terroir implies a strong regional identity, similar to an actual ecosystem. It is the combination of the characteristics of the natural environment and the know-how of the winegrowers that contribute to the typical characteristics of a wine, and at the same time, reveal those of its terroir.

Between the Loire Valley and Burgundy, the vineyards of Sancerre and Pouilly-sur-Loire are a good illustration of this concept of terroir. The recurring question of the role of geology on the typical nature of a wine and thus of a terroir is also relevant here. Opinions have often differed.

However, geology clearly influences the characteristics that define a terroir. The topography, i.e., the relief and its morphology, depends on the type of rocks making up the subsoil and its structure. It is also the relief that partly influences the quality and diversity of the wines, depending on the exposure of the slopes.

Sancerre, a world-renowned terroir with a long geological history.

© BRGM - Nicolas Charles

Millions of years of history

The landscape of Sancerre is characteristic with its hillock on which the village was built. The hill has survived erosion for several thousand centuries thanks to its solid cap of flint conglomerates. These siliceous rocks were deposited in valleys about 40 million years ago! Geologists speak of an inversion of relief, whereby the softer surrounding land (marl and limestone) has been eroded while the harder flint rocks have protected the ground of the Sancerroise and Andelain hills.

A wide variety of wines

Caillottes soil on hard ground, and griottes soil on softer ground, are very stony and warm up more quickly leading to earlier ripening of the grapes with lower acidity and sugar content than the terres blanches soil. Sauvignon provides elegant, light, fruity and perfumed wines with more marked varietal aromas (evoking boxwood or blackcurrant leaf).

Finally, the chailloux, very siliceous ochre-coloured soils that were originally formed under a hot and humid climate by the alteration of Cretaceous rocks, are found on the slopes of the Sancerre and Saint-Andelain hills. They produce wines of varying styles, depending on the proportion of clay in the soil: spicy with a characteristic flinty bouquet.

Alsace, a wine region on the edge of the rift

On the hillside, protected by the Vosges mountains from precipitation and cool winds due to the foehn effect (a warm, dry wind on the leeward side of a mountain blocking a mass of humid air on the windward side), it is a thin green ribbon a few kilometres wide and more than 100 kilometres long that stretches between Mulhouse and Strasbourg. But what a ribbon – its vineyards are located on the geographical borders and geological boundaries of France; welcome to Alsace!

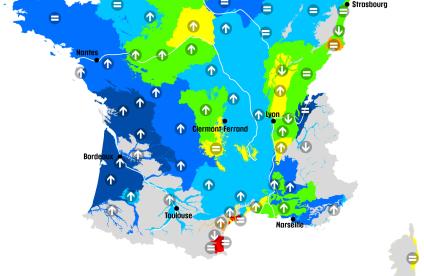

The Alsatian vineyards have a unique position on the edge of a major tectonic structure, the West European Rift, which extends from the North Sea to the Mediterranean. The Rhine Graben, underlying the Alsatian vineyards on its western edge, was mainly formed like its “cousins” the Bresse, Loire or Limagne grabens, during the Oligocene period, about 30 million years ago.

Vineyard of Turkheim, between the Alsace plain and the Vosges mountains.

© BRGM - Nicolas Charles

A vineyard that has come down to us from ancient times

On the edge of the Vosges, the vines are rooted over granite, gneiss or schist foundations. Alsace's geodiversity is thus due to a long geological history, from the Variscan range nearly 350 million years ago to the alluvium that is still deposited in rivers today. Mountains, seas, lagoons, lakes, volcanoes, glaciers and rivers have followed one another in the meanders of time, contributing to the identity of this Alsatian subsoil, which today bears unique vineyards that have been tended for millenia.

Sylvaner or Gewurztraminer?

In Alsace, a balance must be found between ampelographic and geological considerations. Within the many types of rock, the main mineral constituents are quartz (silica sand), clay and limestone. Claude Sittler, a geologist at the University of Strasbourg, has thus proposed a correspondence between the gustatory qualities of Alsatian wines and the mineral elements due to the region's geodiversity. Power and astringency for the clay, vivacity and acidity for the quartz, opulence and mellowness for the limestone. It's all a question of balance between the silica sand which makes the soil porous, the clay which captures water and releases it to the vines, but not too much, and the limestone that delivers mineral elements to the vines gradually, to avoid chlorosis.

The Bordeaux region, with diverse, recent geological formations, between land and sea

Saint-Émilion, Pomerol, Saint-Estèphe, Margaux, Pauillac and Sauternes. These prestigious names are synonymous with some of the most famous wine appellations in the world. While the temperate oceanic climate and its hygrometry, so favourable to vines, confer a certain unity to Bordeaux wines, the geology proves to be much more varied, which partly explains the numerous appellations.

The Bordeaux region, located in the Aquitaine Basin, has a relatively recent subsurface, with mainly calcareous and more or less clayey rocks, the oldest of which are about 50 million years old, and fluvial terraces rich in gravel, pebbles and sand for the most recent. Over the last tens of millions of years, the ocean and rivers have alternated between deposits from multiple marine incursions and sediments torn from the Massif Central and from the Pyrenees by the Garonne, the Dordogne and their tributaries. This alternating ‘to and fro’ process was progressively accompanied by the formation of the Pyrenees and the Alps, as well as by climatic changes that caused the sea level to fluctuate. Two main terroirs can be distinguished: the rocky limestone and more or less clayey soils of the Cenozoic era (66 to 2.6 million years ago), which form the Bordeaux plateaux; and the gravelly and sandy soils of the fluvial terraces (with sediments deposited by rivers) of the Quaternary era, the famous "graves".

Bordeaux vineyards, Château de Barbe - Côtes de Bourg, Villeneuve.

© BRGM - Nicolas Charles

Typical limestone formations

The rocky foundations of the vineyards and landscapes of Bordeaux were formed from the Eocene to the Miocene eras (from 56 to 5.3 million years ago). These rocks are of marine, lacustrine or fluvial origin. The best known are the Blaye limestone, the Saint-Estèphe limestone and, of course, the starfish limestone, which was used to construct the village of Saint-Émilion and underlies the plateaux of the Gironde landscape. The geodiversity of Bordeaux is therefore rich with many different combinations due to the specific characteristics of each terroir (soil, water, topography, climate, grape variety and rootstock, plus winegrower know-how).

The hill of Saint-Émilion

The hill of Saint-Émilion, renowned for its contribution to France’s wine heritage, overlooks the Dordogne valley, where remarkable red wines are produced that are powerful, full-bodied, tannic and age very well. The plateau, at an altitude of 90 m, has a foundation of starfish limestone, whose stones are quarried on site and used in the village. Going downhill, the hillside is then made up of a clay layer with oyster fossils, followed by a carbonate clay of lacustrine origin called the Castillon Formation, resting on a final layer of sandy clays, the Fronsadais molasse.

Burgundy, a kaleidoscope of terroirs with renowned climates

In the east of France, from Auxerre to Mâcon via Dijon and Beaune, an exceptional, world-renowned wine-producing region stretches in a broken chain over nearly 250 kilometres. The Burgundy vineyards produce, among others, the best and most expensive red and white wines in the world. They are divided into six regions including Chablis, Châtillonnais and Grand Auxerrois.

Several episodes in the history of the Earth have contributed to the geodiversity and shape of the topography, as well as the emergence of Burgundy's terroirs, namely tropical seas, the formation of coral reefs, the upheaval and deformation of the subsurface with the birth of the Alps, alteration, erosion and deposition of sediments, and climatic changes in the Quaternary period.

The Roche de Solutré (493 m) consisting of limestone and marl rocks dating from the Jurassic period, which overlooks the vineyards of the Pouilly-Fuissé certified appellation area.

© BRGM - Nicolas Charles

A story of sea, mountains and rivers

The terroirs, essentially clay-limestone ones, were formed by the deposition of marine sediments mainly in the Jurassic period (200 to 150 million years ago) at the bottom of a warm and shallow tropical sea. These are limestone formations containing marly alternations (layers with more clay in them), some of which are quarried and produce beautiful ornamental stones such as the Comblanchien limestone.

The story continues with the birth of the Alps, which changed the architecture of the subsurface about 30 million years ago. During this period, called the Oligocene, the crust of the whole of Western Europe was stretched, giving rise to several fault troughs, including the Bresse trough, which is bordered by a network of meridian faults (oriented generally north-south) delimiting the slopes of the Saône plain (Côte de Beaune, Côte de Nuits, Côte Chalonnaise, Mâconnais, Beaujolais).

Very particular climates

In addition to the geology, the climate is an essential natural factor with respect to the Burgundy vineyards. Predominantly continental, the Burgundian climate can also be influenced by the sea air from the west or the mild Mediterranean air from the south, which influences the quality of the vintages.

The word “climat” has a completely different meaning in Burgundy. Since the Middle Ages, wine producers have gradually and precisely demarcated and named their vineyard plots, thus establishing so-called “climats” or wine growing locations. All of which has nothing to do with the weather! It is particular to Burgundy, which has been classified as a Unesco World Heritage Site since 2015. According to the UNESCO definition, each climat has specific geological, hydrometric and exposure characteristics. The produce from each climat is turned separately into wine from a single grape variety. The wine thus produced takes the name of the climat from which it originates.

Côtes de Provence, 50 geological shades of Rosé

Wine lovers have come to appreciate rosé wine over the last 30 years and it is now as well-known as red and white wines, valued as a refreshing addition to a summer (or any) meal, with family or friends. What better example of rosé wine could one give than Côtes de Provence? The appellation comes from a wide range of terroirs that produce dry and light rosé wines, whose origin is due to a geological history of more than 500 million years.

Just like the various hints to be found in Provençal rosé (peach, melon, mango, grapefruit, tangerine or redcurrant), the minerals of the geology underlying this wine-producing region, introduced by the Phoenicians and the Phoceans some 2,600 years ago, vary just as much: limestone, dolomite, sand, gravels and pebbles, sandstone, marl, pelites, granite, rhyolite, schist, mica schist, migmatite, and gneissic rock. This geodiversity is the result of a long and complex geological history, which is difficult to sum up in a few lines.

Sainte-Victoire, a clay-limestone terroir in Provence limestone.

© BRGM - Nicolas Charles

Today’s Provence landscapes reveal extensive geodiversity

-

Provence crystalline, a region of magmatic and metamorphic rocks, which can be seen in the Maures-Tanneron massifs (Saint-Tropez, Ramatuelle, Porquerolles). These rocks were formed during the Variscan orogeny, when a mountain range was created some 350 million years ago.

-

The Permian depression forms a crescent from Toulon to Fréjus, passing through Vidauban and Roquebrune-sur-Argens. The red soil has evolved from sandstone-clay rocks, the result of erosion of the ancient Variscan chain some 300 million years ago. Added to this are the rhyolites of the Esterel, red volcanic rocks resulting from a major eruption at the same time.

-

Provence limestone, a region of eponymous rocks of marine origin that were formed from the Trias to the Cretaceous (between 250 and 65 million years ago). These rocks, folded and faulted in an east-west direction during the formation of the Pyrenees nearly 40 million years ago, make up the principal mountains of Provence such as Sainte-Victoire or Sainte-Baume, but also the Beausset basin, from Cassis to Bandol.

Rosé accounts for 90% of the wines produced in the region

As a result of the extent and diversity of the terroirs, the wines of the Côtes de Provence appellation (which have the AOC label since 1977, covering nearly 20,000 hectares) each have their own geological and climatic personality. The appellation is traditionally broken down into eight basins: the Bordure Maritime, Notre-Dame-des-Anges, the Haut Pays, the Bassin du Beausset, Mont Sainte-Victoire, Fréjus, La Londe and Pierrefeu.

More than 90% of the wines produced here are rosé, and the appellation features various grape varieties typical of the south such as Syrah, Grenache, Mourvèdre, Cinsaut and the Var grape, Tibouren. Carignan and Cabernet-Sauvignon complete the range of rosé and red wines. Nor should we neglect the white wines, which are certainly in the minority but which use the Rolle, Ugni blanc, Sémillon and Clairette varieties of grape.