Fête de la science 2022: climate change

The Fête de la science, a popular flagship event that celebrates the sharing of science, will take place from 7 to 17 October 2022 in mainland France and from 10 to 27 November in the overseas territories and internationally.

Organised each year by the Ministry of Higher Education and Research, the Fête de la science is a must for all audiences. Over ten days, families, schoolchildren, students, amateurs and science enthusiasts exchange ideas at thousands of free events organised throughout France.

To launch its 31st edition, the Fête de la science is taking place at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (National Natural History Museum) in Paris. An exceptional event, free and open to all, will be held from 7 to 9 October in the Grande Galerie de l'Évolution. This is an opportunity for young and old alike to talk directly to scientists and to take part in debates and numerous activities. And so that you can follow the event from your sofa, a series of programmes will be hosted by Fred Courant of the popular TV programme L'Esprit Sorcier and broadcast live on the Fête de la science website and on those of all the partner research operators.

BRGM, the national geological survey, will take part in the Fête de la science in Paris, Orléans and throughout France.

Science Live 2022: What is urban resilience?

Climate change, a hot topic

This year, the Fête de la science will focus on a topic that is central to the concerns of today's and tomorrow's citizens: climate change.

More than ever, the climate is now the focus of dialogue between science and society, as evidenced by the IPCC reports, COP 27 and the World Ocean Summit. At the current rate of development, global warming will undeniably have environmental, but also economic and social consequences. The situation is certainly alarming, but what can be done? What solutions can be found?

To answer all these questions, research, mediation and scientific culture professionals invite you to a cross-disciplinary discussion on their work and the innovations that may help us mitigate our impact on the environment.

Gilles Grandjean, BRGM ambassador

Paris, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle (National Natural History Museum): Science Live, 7 October 2022, 17:00 to 17:35

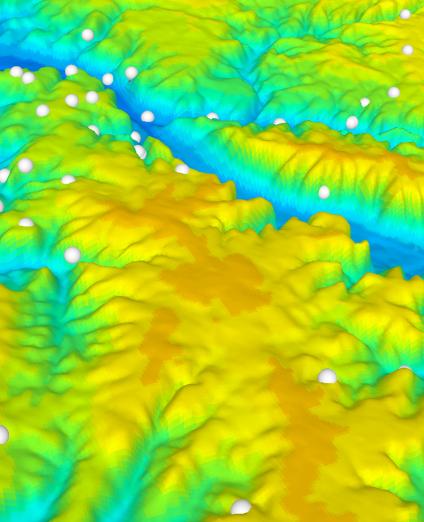

The impact of climate change on natural hazards. How to adapt?

Speakers: Gilles Grandjean, BRGM Ambassador, and Xenia Philippenko-Crnokrak.

Orléans: science village, 8 and 9 October 2022

"Geothermal energy: energy for the future" stand, from 10 am to 6 pm.

Presentation of geothermal energy and its various applications.

Angers: ESEO (engineering school), 15 October 2022

"Services provided by soils and nature in counteracting climate change", lecture by Cécile Le Guern.

Nantes: Nantes Métropole Eco-Neighbourhood, Wednesday 12 and Saturday 15 October 2022

"Soil sealing: an asset in the face of climate change?", lecture by Cécile Le Guern

Soil is a precious and fragile resource that must be preserved. To counteract soil artificialisation, more and more initiatives are being taken to make urban soils permeable. What is the benefit of making soils permeable in the face of climate change? What can nature-based solutions contribute? Can soils be made permeable everywhere? How to choose the most relevant locations.

Reims, 7 and 8 October 2022

Stand: Regional geology, risks and resources

Presentation of a snakes-and-ladders-type game on mineral resources, an exhibition on cavities on geological maps, different types of rocks and work carried out by BRGM.

Bastia: Casa di e scenze, 12 October 2022 (afternoon)

Workshop: Climate change is also affecting beaches and mountains. What are the risks?

BRGM Corsica presents its interactive, creative workshop on natural hazards on the coast and in the mountains. Come and follow the story of a family adapting its living space to climate change! The model presented during the BRGM workshop will help you find out about the different coastal and mountain hazards that can be found in Corsica. To illustrate this, a family will travel through the villages to escape the natural hazards. But beware, climate change could disrupt their journey and make their task more difficult!

Reunion Island: Cité du Volcan and Faculty of Sciences of Saint-Denis, 10 November 2022

Presentation of models and posters, fun activity for children under 12 (game of goose / Trivial pursues) on the activities of the BRGM (coastal risks, earth movements, groundwater).