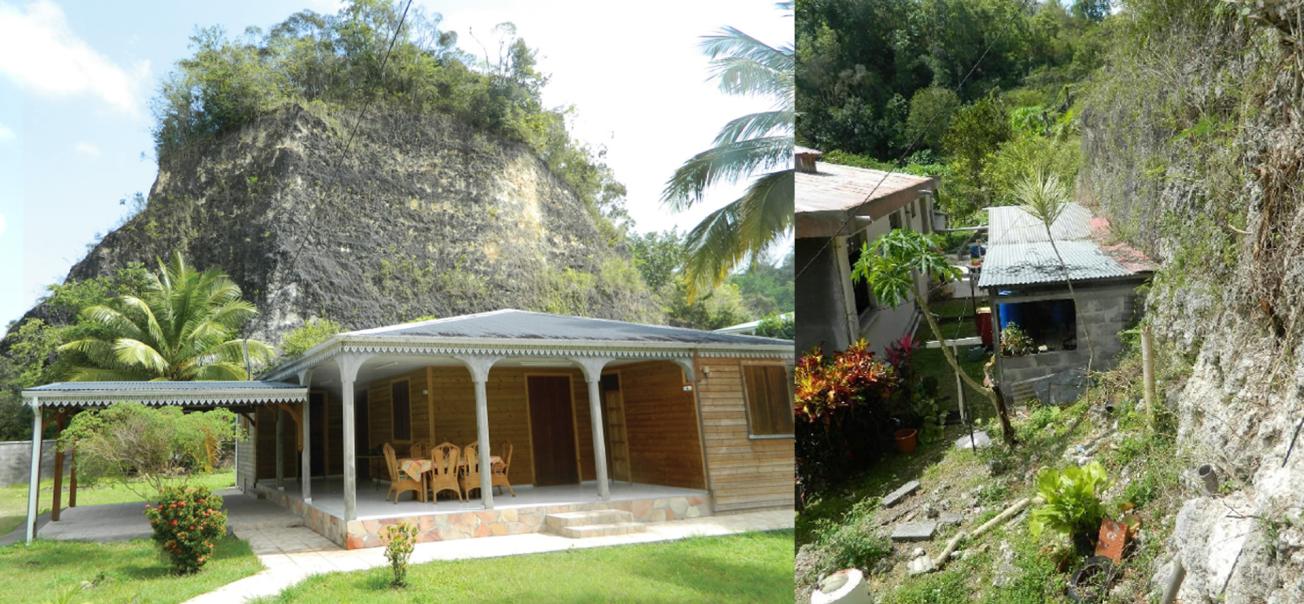

Examples of recent urban development in former quarries (Grands-Fonds, Guadeloupe, 2020).

© BRGM

The need

In Guadeloupe, and especially in Grands-Fonds, Grande-Terre, many legal or illegal quarries are abandoned without being secured or rehabilitated. These quarries do not have an identified owner.

The authorities asked BRGM to carry out a study on securing the wall faces of abandoned carbonate rock quarries in Grande-Terre. Numerous cliffs of varying sizes in Grands-Fonds have been forgotten or are concealed by vegetation. But because of urban development, some of these may be incorporated into future schemes and could pose a risk to people’s homes.

The results

The first stage of this study involved identifying the various abandoned quarries dating back from before 1999 and which have not been secured or rehabilitated. A database was built comprising 75 sites with known, described and geolocalised wall faces.

The second step was to develop a generic, easily applicable methodology for assessing and classifying the various sites, and to establish an initial hierarchy of risks. The methodology is based on defining several easily applicable criteria relating to the magnitude of risks (typology, distance to the wall face) and geometry of the wall face (height, presence of steps, appearance). Seven “reference” scenarios were defined covering several potential events, with a “long-term” time frame of approximately 100 years:

- S0 – Falling of rocks and small blocks;

- S1 – “Crumbling” of friable formations – falling of superficial flaky material;

- S2a – Falling of boulders (larger pieces);

- S2b – Boulders from the slope above the cliff face becoming loose;

- S3 – “Crumbling” of friable carbonate formations, with slabs coming off that are larger or thicker than for S1;

- S4 – Falling of blocks higher up on a slope covered with vegetation;

- S5 – Breaking off of large structural components forming part of the quarry face or within less clearly identifiable levels.

Lastly, forty sites were analysed in more detail and recommendations were made for securing the quarries and managing risks. Available information, including the classification, reference scenarios and additional data for individual sites, was summarised with supporting photos.

Using the results

The methodology developed for this study was used to determine several key strategies for securing the quarries based on wall face typology and different reference scenarios. While this is not a substitute for the detailed mapping of the hazard and associated risks and the detailed design of suitable remedial actions, it provides an initial, generic characterisation and interpretation of the hazard of falling blocks for use by government agencies and municipal technical departments.

The partners

- DEAL Guadeloupe

- Communes of Pointe-à-Pitre, Le Gosier, Sainte-Anne, Le Moule, Morne-à-l’Eau and Les Abymes