Former industrial sites and schools

Transcription

Former industrial sites and schools

Like most industrialised countries, France inherited a long industrial past during which environmental preoccupations and constraints were not the same as today's. Urban landscapes have evolved and industrial zones, which used to be on city outskirts, have been caught up by urbanisation. Businesses located in city centres, such as dry-cleaners, woodworking shops and service stations, handled products that could have accumulated in the ground.

The effects of these substances were unknown back then. Yet, some have turned out to be harmful to human health. Nowadays, houses, vegetable gardens, parks and even schools, may have been built on such sites without knowing what previous activities took place there. Since 1996, an historical inventory of industrial services and sites has been requested by the Ministry in charge of Sustainable Development. This inventory includes around 300,000 sites, but is not exhaustive. The Basias database provides much information about past activities. However, it cannot tell us which products were used or the actual state of the soil. This soil can either be healthy or polluted. The second French environmental health plan foresees to reduce exposure in buildings welcoming children. As such, the state has undertaken a project to check the quality of buildings welcoming young people that were built on or near former industrial sites.

Which schools are concerned by this plan?

Before examining quality of life, we must first identify all buildings potentially affected by this historical pollution. And it's not that easy.

Mr. Koch-Mathian, hello. Can you explain how the list of schools was set up?

The assessment occurs by crossing two databases. The database of former industrial sites, called Basias, and those of institutions welcoming so-called sensitive populations. In this example, we have a school where the playground was extended upon the site of an old building which was a former service station.

Are these schools necessarily situated on former industrial sites?

There are two types of schools: either built on or having a shared boundary.

Is the list you compiled after your location spotting final?

No, it isn't final. Once this list is published, local representatives can supply additional information.

Does the plan concern all of France?

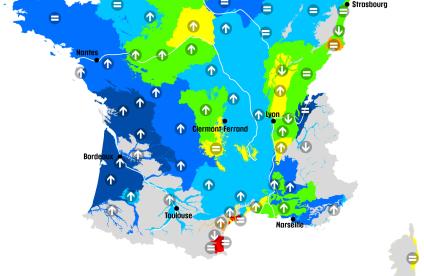

Yes, it concerns the whole of France. A first list concerning 70 districts was finished in 2010. The remaining districts are covered by a second list finalised late 2012.

Why did the second list take longer?

The inventory of former Basias industrial sites wasn't complete in certain highly industrial zones which were also highly urban, with many schools.

And the Rhône-Alpes region?

This region is concerned by our plan. The spotting and crossing tasks are currently underway and will allow us to make a third list which will be published later. Once the list of schools is finalised, research units are appointed by the BRGM to carry out diagnoses.

What are the steps of a diagnosis in a school?

- Anne-Marine Robert, hello.

- Hello.

What does the first phase of the diagnosis consist in?

The first phase consists in leading two simultaneous studies. On the one hand, a historical research on the plot of the school and its surroundings, and, on the other hand, an in-depth visit of the school to determine the layout of the buildings and the school's uses of them.

Concretely, what do you look for in this first phase?

We aim to trace former polluting activities, locate them within the school, and determine the typology of pollutions.

We also try to understand the behaviour of groundwater beneath the school. And, for the visit of the school, we aim to locate classrooms and official accommodations, and to understand how each building is laid out. Whether there is crawl space or not, a basement, and so on. As for outdoor areas, we try to identify bare soil zones, and any vegetable or educational gardens.

The historical and documentation study and the visit will allow to conclude that the school's current layout doesn't pose a problem or that it requires, due to the uncertainties, further investigations in the school's vicinity.

The diagnosis can be made once we have enough information to either exclude the school from our plan, for instance, if the Basias, the industrial building, is far away from the school, and not superimposed or adjacent, or if the data shows that the children are not exposed to substances from this former industrial building.

In cases where doubts remain, researchers go back to the school to take measures and samples.

In phase two, what measures do you take?

Our measures are linked to the results of the 1st phase of diagnosis, that is the relevant zones we've identified. For example, surface soil or tap water. For the air, we look at the air that comes before internal air. This means air under building slabs, or in crawl spaces and basements, or air one metre deep from the ground alongside the buildings.

We also take samples of water in a well if there is one, or from fruit and vegetables grown on the schoolgrounds.

As you can see, this investigation phase will reach a conclusion in the vast majority of cases. However, if doubts remain as to the air quality inside the buildings, additional investigations will be necessary.

If measurements on areas prior to exposure, meaning the ground under the slabs, display potentially dangerous content, internal air measurements will be undertaken. These will finalise the diagnosis of the school.

Then what?

After this diagnosis, schools can be classified in 3 categories. One, the school's soil shows no problems. Two, the current amenities and uses protect people from exposure to pollutions, whether these pollutions are potential or proven. Three, the diagnoses show the presence of pollutions requiring the implementation of technical measures, or even public health measures.

In light of these different categories, the feedback in September 2012 for 397 schools, shows the following distribution: 3% of schools are not concerned by our plan. 65% are classified in category A. 30% are classified in category B. And in the end, only 2% of schools are classified in category C.

If there is pollution, is it worrying?

In the event of oil or metals in the soil, we can either cover the soil with clean soil or replace it completely. If the diagnoses show the presence of pollution in the internal air, there are different solutions. Air out the premises every day. Make the floor watertight. Pump the soil air out from under the slab to stop it from going up into the buildings.

Whatever the case, if a pollution is identified, measures are taken so that it doesn't affect living spaces.

To this day, no health or safety treatment has been necessary.

Since 2010, the diagnoses have confirmed the interest of this plan, which is an objective and rational solution to improve quality of life. Compiling this environmental memory can only occur gradually, over several years.

Interministerial management, the involvement of local representatives, and adapted information provided early on for school staff, students and parents, made the project run smoothly.

Based on this experience, diagnoses were planned in 2013 in the 21 districts concerned by the second wave.