Coastline management on the sandy coast of the Occitanie region – Short version

Transcription

The shoreline is a frontier, the place where earth, sea and sky meet. It's a mix of elements with individual characteristics whose complex interaction enables the coastline to be mapped.

The coastline or shoreline is difficult to define: it's the interface between sand and sea.

The coastline, by its nature, changes and fluctuates, shifting over time, according to the seasons and weather.

We often hear about "coastal erosion". This is not a recent phenomenon, but it has accelerated in recent decades.

It's due to the action of the waves dragging sediment along the beaches. That's coastal erosion.

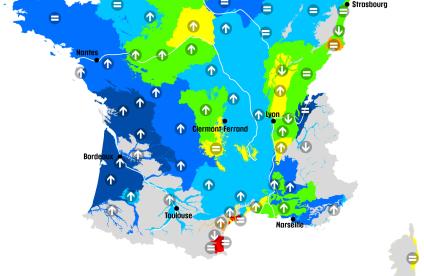

It can be seen in various forms, and is present along most of France's coastline. The causes are natural phenomena linked with human factors. Its consequences are barely perceptible day to day, but storms, by spectacularly accelerating the erosion, regularly remind us of the fragility of coastal areas.

Everyone likes the seaside, but its apparent simplicity hides a complex structure and operation. Here comes Yann Baloin from the BRGM, who will explain. Hello, Yann.

Hello, Vincent.

Can you explain how the beach-dune system works?

The beach-dune system consists of 3 interdependent compartments between which sand is carried by the wind, the swells and the waves. The first compartment is the underwater beach, on which are found pre-coastal sand banks. Then comes the exposed beach where you put your towel. Lastly, the dune bank containing large amounts of sand.

Right. Mediterranean tides are minimal, so what causes the sand to move?

The main evolutionary factors are the swell created by the wind, and the wind itself that moves the sand. There are also the extreme levels caused by storms. The waves are generated by the wind. At sea and on the ocean, they build up freely: that's a swell. As the waves arrive at the shore, they break up, resulting in currents of various types. First we have currents that go from the sea to the land, which allow sand to accumulate: this is called accretion. Then there are return currents, which carry material towards the sea. It's mainly these currents that cause seasonal variation. In winter, sand is dragged towards the pre-coastal bars. In spring, we have more favourable currents that replenish the beach with sand. The breaking of the waves as they approach the coast creates a current parallel to the coastline, the coastal drift. This phenomenon plays the main role in how beaches evolve in terms of accretion, erosion and coastal stability.

Does installing protective structures along the coast change the currents?

Locally they can disturb the sand movements, and paradoxically accentuate erosion on adjacent coastlines.

To quantify the accretion or erosion of a coast, we need to count the volume of sand involved. When you look at a sketch of the coast, you can have an estuary, a port system or a rocky coastline. We can divide the coastal system into several compartments, which are relatively independent from each other, and within which we can calculate the level of sedimentation. To do this, we make use of 3 parameters. The first is the sand entering this compartment.

This comes mainly from the riverbanks via the estuary. Sand is also brought in by the sea. The second parameter is sediment leaks, i.e. losses from this compartment, either towards the lagoon during major storms, or towards the sea with the return current. Lastly, we need to know the amount of sediment already present in the cell, and in particular the depth of the sand inside that cell. Now we know the sediment level in the compartment, and we can assess the shoreline's erosion or accretion levels.

It's better not to react immediately after a storm, but to take time to analyse it.

Normally the beach repairs itself naturally, regaining most of its sand after a few weeks. This is known as resilience.

The Languedoc shoreline consists of low sandy beaches and coastal bars, strips of land separating a lagoon from the sea.

On this type of coastline, particular conditions apply. Firstly, tides are minimal: a maximum of 30cm on average. Secondly, drifting often occurs, caused by atmospheric pressure and the wind and waves during storms.

High winds, low-lying land and narrow bars: the Languedoc coast is a vulnerable space, and the sediment levels of the cells can be impacted by natural phenomena and human activity.

The natural phenomena which affect the coast are storms, which can cause submersion and coastal erosion.

Human activity includes sand extraction, sand pits, mechanical beach cleaning, dune levelling and urbanisation in general. But the biggest impact on coastal evolution is the development of riverbanks and in particular riverbeds. In their natural state, rivers convey to the coast sediment from the erosion of the riverbanks, contributing to the sediment levels on the beaches. But the construction of dams and embankments, as well as the practice of dredging the rivers, have progressively blocked the sediment, depriving the beaches of sand. In former times, man adapted to coastal fluctuations by not permanently inhabiting land close to the sea. But industrial development and tourism during the 1950s and 60s altered the coastal landscape.

In 1963, the Racine initiative, named after the person in charge, instigated the development of tourism on the Languedoc-Roussillon coast, involving large-scale building works.

In its wake, many sites devoted to seaside tourism or industry were built. These areas played a major role in the dynamic balance of the coastal system. For example, dune banks disappeared, and others appeared at sea level.

Thereafter, coastal fluctuation was no longer deemed possible, as large swathes of the economy depended on its permanence. To ensure this, many structures were built: longitudinal defences high up the beach, such as walls, boulders and rip-rap, and breakwaters or groynes close to the shore to protect the dunes from the sea and stop the coastline moving.

But their presence increases the action of the swell, accentuating the phenomenon of erosion in front of the structure, known as undermining. They also reduce the profile of the beach, making it narrower, and increase the erosion in unprotected zones on either side of the structure. Transversal structures such as groynes are intended partly to prevent sedimentation due to coastal drift. However, they block not only the coastal drift, but the natural transit of sediment. They create an accretion zone upstream, and an erosion zone downstream due to lack of sediment. When arranged in banks, they can heavily modify the currents from coast to sea, causing increased erosion between each groyne and a lowering of the seashore. While these measures are often said to be necessary given the economic issues, it is now vital that we fine-tune our actions on the coast to protect it from erosion. Individual interventions done in a rush have now been replaced by a deeper, more global approach to the situation.

This new way of managing the coast is required by the national strategy for integrated coastal management, adopted by the government in 2012.

There now exists a raft of new techniques which vary in scale and affordability. But none is a one-off, miracle solution. As each context is different, projects must be appropriate and take into account the lifetime of the structures.

The coastline is a dynamic, living space. It is sometimes spectacularly changed after a storm. Faced with the phenomenon of coastal erosion and submersion, there is no miracle solution. We must continually strengthen our knowledge of how the coast works. Observing phenomena will help us build, on a local scale, appropriate solutions which take into account human and economic issues as well as our natural heritage. For a long time, we thought that building sea defences was a permanent solution. Today, we understand it was just a temporary one. From now on, we must think differently about the land and how we use it, reconstructing coastal areas at risk of erosion and submersion. We must act today to preserve the attractiveness and the way of life of tomorrow's coastline.

Coastline management on the sandy coast of the Occitanie region – Long version

Transcription

The shoreline is a frontier, the place where earth, sea and sky meet. It's a mix of elements with individual characteristics whose complex interaction enables the coastline to be mapped.

The coastline or shoreline is difficult to define: it's the interface between sand and sea.

The coastline, by its nature, changes and fluctuates, shifting over time, according to the seasons and weather.

We often hear about "coastal erosion". This is not a recent phenomenon, but it has accelerated in recent decades. It's due to the action of the waves dragging sediment along the beaches. That's coastal erosion.

It can be seen in various forms, and is present along most of France's coastline. The causes are natural phenomena linked with human factors. Its consequences are barely perceptible day to day, but storms, by spectacularly accelerating the erosion, regularly remind us of the fragility of coastal areas.

Everyone likes the seaside, but its apparent simplicity hides a complex structure and operation. Here comes Yann Baloin from the BRGM, who will explain. Hello, Yann.

Hello, Vincent.

Can you explain how the beach-dune system works?

The beach-dune system consists of 3 interdependent compartments between which sand is carried by the wind, the swells and the waves. The first compartment is the underwater beach, on which are found pre-coastal sand banks.

Then comes the exposed beach where you put your towel. Lastly, the dune bank containing large amounts of sand.

Right. Mediterranean tides are minimal, so what causes the sand to move?

The main evolutionary factors are the swell created by the wind, and the wind itself that moves the sand. There are also the extreme levels caused by storms.

The waves are generated by the wind. At sea and on the ocean, they build up freely: that's a swell. As the waves arrive at the shore, they break up, resulting in currents of various types. First we have currents that go from the sea to the land, which allow sand to accumulate: this is called accretion. Then there are return currents, which carry material towards the sea. It's mainly these currents that cause seasonal variation. In winter, sand is dragged towards the pre-coastal bars. In spring, we have more favourable currents that replenish the beach with sand.

The breaking of the waves as they approach the coast creates a current parallel to the coastline, the coastal drift.

This phenomenon plays the main role in how beaches evolve in terms of accretion, erosion and coastal stability.

Does installing protective structures along the coast change the currents?

Locally they can disturb the sand movements, and paradoxically accentuate erosion on adjacent coastlines.

To quantify the accretion or erosion of a coast, we need to count the volume of sand involved. When you look at a sketch of the coast, you can have an estuary, a port system or a rocky coastline. We can divide the coastal system into several compartments, which are relatively independent from each other, and within which we can calculate the level of sedimentation. To do this, we make use of 3 parameters. The first is the sand entering this compartment.

This comes mainly from the riverbanks via the estuary. Sand is also brought in by the sea. The second parameter is sediment leaks, i.e. losses from this compartment, either towards the lagoon during major storms, or towards the sea with the return current. Lastly, we need to know the amount of sediment already present in the cell, and in particular the depth of the sand inside that cell. Now we know the sediment level in the compartment, and we can assess the shoreline's erosion or accretion levels.

It's better not to react immediately after a storm, but to take time to analyse it.

Normally the beach repairs itself naturally, regaining most of its sand after a few weeks. This is known as resilience.

The Languedoc shoreline consists of low sandy beaches and coastal bars, strips of land separating a lagoon from the sea.

On this type of coastline, particular conditions apply. Firstly, tides are minimal: a maximum of 30cm on average. Secondly, drifting often occurs, caused by atmospheric pressure and the wind and waves during storms.

High winds, low-lying land and narrow bars: the Languedoc coast is a vulnerable space, and the sediment levels of the cells can be impacted by natural phenomena and human activity.

The natural phenomena which affect the coast are storms, which can cause submersion and coastal erosion. Human activity includes sand extraction, sand pits, mechanical beach cleaning, dune levelling and urbanisation in general. But the biggest impact on coastal evolution is the development of riverbanks and in particular riverbeds. In their natural state, rivers convey to the coast sediment from the erosion of the riverbanks, contributing to the sediment levels on the beaches. But the construction of dams and embankments, as well as the practice of dredging the rivers, have progressively blocked the sediment, depriving the beaches of sand. Between 1960 and 2000, the population of Languedoc-Roussillon increased by 1 million. Today, the coast remains attractive and the region's demographic growth continues apace. One consequence of the population growth is the development of the coast, leading to more protection issues. In former times, man adapted to coastal fluctuations by not permanently inhabiting land close to the sea. But industrial development and tourism during the 1950s and 60s altered the coastal landscape.

In 1963, the Racine initiative, named after the person in charge, instigated the development of tourism on the Languedoc-Roussillon coast, involving large-scale building works.

In its wake, many sites devoted to seaside tourism or industry were built. These areas played a major role in the dynamic balance of the coastal system. For example, dune banks disappeared, and others appeared at sea level.

Thereafter, coastal fluctuation was no longer deemed possible, as large swathes of the economy depended on its permanence. To ensure this, many structures were built: longitudinal defences high up the beach, such as walls, boulders and rip-rap, and breakwaters or groynes close to the shore to protect the dunes from the sea and stop the coastline moving.

But their presence increases the action of the swell, accentuating the phenomenon of erosion in front of the structure, known as undermining. They also reduce the profile of the beach, making it narrower, and increase the erosion in unprotected zones on either side of the structure. Transversal structures such as groynes are intended partly to prevent sedimentation due to coastal drift. However, they block not only the coastal drift, but the natural transit of sediment. They create an accretion zone upstream, and an erosion zone downstream due to lack of sediment.

When arranged in banks, they can heavily modify the currents from coast to sea, causing increased erosion between each groyne and a lowering of the seashore.

Despite the success of some measures, the global, environmental and economic outlook is mixed.

On the coast, we mostly see so-called hard measures. Is that the path the marine nature reserve wants to take?

Not at all. With 4,000km², 100km of coastline, the marine nature reserve is charged with managing public maritime areas. Its aim is to plan over 15 years, but it has to work with all the local stakeholders, with the support of a team of professionals qualified in all aspects of the sea. Therefore we need to work in a modern, democratic and local way, so that, with the government, we can support all projects and reflect on all known problems. The results are obvious.

The people are motivated, they're committed, they want us to preserve the heritage and the culture of the Mediterranean, and the coastline is part of that approach.

Between defending the coast and accepting its retreat, the former option has, up to now, been adopted.

While these measures are often said to be necessary given the economic issues, it is now vital that we fine-tune our actions on the coast to protect it from erosion. Individual interventions done in a rush have now been replaced by a deeper, more global approach to the situation. This is even more necessary given that climate change could exacerbate the problems. This new way of managing the coast is required by the national strategy for integrated coastal management.

The national strategy for integrated coastal management, adopted by the Environment Ministry in 2012, constitutes a true roadmap shared between the government and local authorities based on knowledge and local strategy to include coastal erosion in public policy. This strategy aims to rethink the development of the area using flexible techniques for managing the coastline, stopping the setting up of businesses in sectors where coastal risks are highest or by relocating their activities when it proves inevitable in a spirit of risk prevention and sustainable development.

There now exists a raft of new techniques which vary in scale and affordability. But none is a one-off, miracle solution.

As each context is different, projects must be appropriate and take into account the lifetime of the structures.

Year on year, we saw this bar, a very narrow strip of sand between the sea and the Étang de Thau, getting thinner, so it was necessary to reconstruct the beach. We had to move back the existing road and reinstate the dune bank.

In some places we were unable to move far enough back, so we had to build so-called "swell attenuators": submerged breakwaters that don't spoil the view of the horizon when you're lying on the fine sand. They're situated 350m from the coast, so that the winter swells are broken, and instead of hitting the rip-rap of the old road, deposit sediment from offshore and return out to sea without dragging away the sediment that's been deposited. So that is the result, and in just 3 years, we've seen the beach grow by over a metre. It's a real benefit. We had to partially refill the beach, and more than 400,000m³ were sourced locally, with the same geological origin and the same granulometry. It's an exemplary European project. The 55-million-euro investment fulfilled a need: the economy, tourism, the protection of nature. A series of actions which together preserve the environment and the economy in this area.

Combining these two things can be particularly difficult in some cases.

In Vias, the dune bank no longer existed, because the campsites and housing had been moving closer to the water for decades. So the aim of this project is to reinstate a natural beach with a sedimentary system on a cellular scale. Initially there was a phase of building works, which you will have seen: reinstating the dune ridge, replenishing the beaches by means of the transfer of sediment. In parallel, we're working in the long term on spatial recomposition at a town-planning level, and the town of Vias is engaged in that. How can we adapt to the risks? So it's a large-scale project. The overall works will cost 30 million euros. It's important to have solidarity along the coast, as what happens upstream has consequences downstream. That's the ethos we have now. We can no longer do what we did for decades, looking only on our own doorstep and not thinking about others. So this project truly represents that coastal solidarity.

The state of some parts of the coast and the need to maintain the shoreline increasingly require inter-community dialogue.

We've been addressing the coastline for many years. At first, we did this individually within towns. Then the government became more demanding, requiring an urban-development plan. So we set up an urban-community department, including a coastal observatory which allows us to take regular measurements and have all the right information when presenting our case for protection. The issues vary according to the type of erosion. There is "soft" protection, places that need protecting, in particular those areas where there are still dunes, where we erect picket fences to enable the dune to reform. Then, there are more important issues concerning the protection of homes and people. This is "hard" protection: breakwaters, rip-rap, refilling beaches. We've been doing that every year for about a decade.

Just like the spatial element, the question of time is a key factor in the success of these operations.

Coastal protection is a long-term phenomenon. It's not: "I'll protect it today and see what happens." You need a forward-looking take on the problem. In some areas, we've had to... not abandon the coastline, but think in terms of long-term protection. In natural areas, like the one where we are, the lido du petit et grand Travers, there have been two major projects: refilling to bring in materials, and the renaturation of the site. We were asked to work on moving back the road, which disturbed the site. That is why we got rid of the road and recreated... The elected officials wanted the site to remain a free tourist attraction. So we kept the site's accessibility whilst improving its natural processes. We removed the road, brought in sand, and we're looking at how the site is behaving and how nature is fighting back, as our ambition was to encourage nature to reinvest without depriving people of the space.

So you've restored the natural processes by extending the dunes, the dune bank.

Yes, the dune bank is now deeper, and can move according to how violent the sea is. There is material to encourage growth. They say that a beach has three parts: a dune ridge, an exposed beach and a submerged beach. Now there is depth to cope better with the sea's violence.

There are various techniques for rehabilitating dunes. First, erecting picket fences to prevent trampling. They also act as wind breaks and encourage sand deposits. Second, the reintroduction of plant matter. The development of plant cover is the best way to ensure the sand stays where it is.

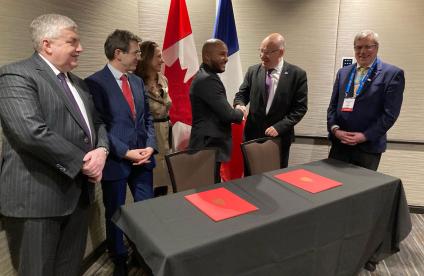

Armed with this experience, the authorities are launching Plan Littoral 21 for Occitanie. The plan makes the coastline central to the region's appeal, and, in terms of coastal management, retains the main points of the national strategy.

The development of Occitanie's coastline, unlike many other regions, is the result of the government looking to highlight its tourism potential which is as yet untapped, by implementing a comprehensive development policy.

The Racine initiative, launched in 1963, was one of the largest tourism and development projects ever undertaken in France and in Europe in the postwar period. These large holiday resorts epitomise modernity, providing an urban solution to the expansion of tourism and the preservation of natural spaces, prefiguring the inception of the Conservatoire du littoral. A new ambitious programme such as the Racine initiative must now be put in place. As the Prefect of Occitanie, I will ensure the operational coordination of these measures.

The Racine initiative disrupted our coastline by creating around 20 resorts with marinas comprising 30,000 moorings.

It was important, given that our region attracts 55,000 inhabitants a year with 5 million tourists on the coast, to look at restructuring, so Plan Littoral 21 was born, with the political will of Carole Delga, signed by the Prime Minister and co-managed by the public-funds authority. The plan contains three strategic pillars. Firstly, ecological resilience, creating a showcase here in France. The second pillar is the economy which drives the region. The third is the idea is that of living together: social cohesion in a region that needed to rediscover its virtues. The issues are manifold, but I'll focus on two or three: climate change, erosion, submersion and the risk-prevention plan. We must also provide a real solution as part of our strategy, but also that of the government regarding the sea and the coast. It now falls to us to build on what was previously done in the resorts, taking into account the fragile biodiversity of 40,000 hectares of lagoon. It's vital for Plan Littoral 21 to take that on board. The two examples that come to mind are, firstly, le grand Castelou, a large expanse of land owned by the Conservatoire. Narbonne is managing this project, helped by local authorities, with the aim of creating a reference for biodiversity, as well as a Narbonne nature reserve. The second issue is how to create a new habitat that will transform the image and identity of the Occitanie region.

The coastline is a key element in the appeal and identity of Occitanie. The region's 215km of shoreline are subject to severe erosion. We must protect the diversity of use, especially sea fishing and farming, and preserve sensitive natural spaces such as lagoons, the properties of the Conservatoire du littoral and the Golfe du Lion marine reserve.

The questions surrounding the occupation of the fragile and highly coveted coast require a more comprehensive approach in order to adapt the use of coastal spaces in the face of the risk of erosion and submersion.

The coastline is a dynamic, living space. It is sometimes spectacularly changed after a storm. Faced with the phenomenon of coastal erosion and submersion, there is no miracle solution. We must continually strengthen our knowledge of how the coast works. Observing phenomena will help us build, on a local scale, appropriate solutions which take into account human and economic issues as well as our natural heritage. For a long time, we thought that building sea defences was a permanent solution. Today, we understand it was just a temporary one. From now on, we must think differently about the land and how we use it, reconstructing coastal areas at risk of erosion and submersion. We must act today to preserve the attractiveness and the way of life of tomorrow's coastline.