Virtual reality tour of an underground cavity

Transcription

So I just left the Forum des Halles. I'm at the BRGM booth with Sylvain. You here?

Yes. Hi, Fred. I'm here.

You know, we're going to take everyone down to a cave.

Science Live!

The Sorcerer's Research

It's not a cave but an underground quarry. You're visiting a quarry that was dug to build the city of Orléans. You're 10 m beneath Orléans town centre.

I'm 10 m beneath Orléans?

That's right. OK.

I can go forward like this, and when I'm walking in the cave, I have all this information about the history... I can see the traces of the quarry workers. We can stroll around. I think there was some gardening in here, too.

They grew lettuce. It was used as a shelter during the war to protect people from bombs. So you can trace the quarry's whole history in a matter of minutes.

I'm in the dark. It's making me dizzy. Tell us about it and how you created, how the BRGM team created, this simulation, this immersion.

There's a 3-D model that is the basis of this immersion. It was created with hundreds of photos taken in a real quarry.

So you went down to take photos.

This quarry wasn't created from scratch, it really exists. And using special software, we recreated a 3-D model, then we added the information about the history.

It's really fun, it's for the general public, but what was your goal in creating it?

Actually, our goal was to raise awareness. In practice, our work focuses on cave-in risks. So a town centre area is of special interest. For that we use another tool, which is right here, the scanner you can't see since you have your viewer on.

Wait. I'll come back up.

OK. That's better.

Well, it was a nice trip. If you're here, check it out. We play with it, but you work with it.

Exactly. Our job is to evaluate the cave-in risks at these quarries and to use the scanner for that.

So it was done specifically in Orléans, to survey the town centre and assess the cave-in risk?

The 3-D model allows us to situate the quarry in relation to the buildings above it, and we can see if there are areas of the quarry in danger of caving in right under the houses.

One of BRGM's main missions in France, among others, is locating natural and manmade cavities that present a danger to the surroundings.

It's one of BRGM's many missions. We maintain a national database of underground cavities, which includes over 180,000 cavities today.

How many?

Over 180,000 across France.

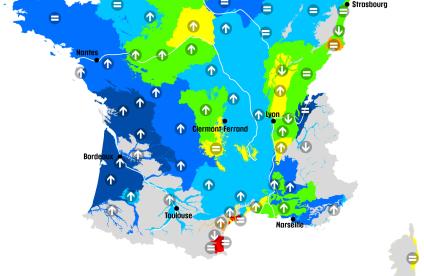

Are certain regions more impacted? That might interest our audience. They mustn't panic! It's your job to locate them.

There are cavities all over. They are under big cities for historic reasons.

Because we dug quarries.

Exactly. We dug them to build cities. We have beautiful Haussmann buildings behind us.

We know that in Paris...

This stone initially was mined under Paris, but later it came from Picardie as the city continued to grow.

Historically, in every city, you could find them...

In almost every city. Some have more. They exist in Paris, of course, but also in Lille and Strasbourg. In Strasbourg, the subsurface was used by breweries to store and brew beer. In that case, you can trace the history by searching archives to locate those quarries, but what do you do about the natural ones?

When it's natural and there's no hole in the ground, we have geophysical methods for detecting them from the surface.

In simple terms, what do you do?

We place an instrument on the ground, which measures the earth's field of gravity.

As a reminder, that's what holds us down.

It's gravity. We see the influence of the underground cavity on the gravity reading.

When there's less mass, there's less gravity? We can't feel it, but your instrument detects it.

We measure the gravity very carefully and repeat it across a whole area to detect areas with abnormal gravity, which might indicate a cavity.

And what's that?

That's a little scanner. This is for when we go down into the cavity ourselves. For the past few years, we've been using this scanner.

Do you hold it like so?

That's right. I'll disconnect it. Without dropping it. Can you hold my mic?

And how do you use it?

We walk around with the scanner. It creates a 3-D model of the cavity as we walk through it.

To create images afterwards?

To recreate the geometry of the cave or the quarry and to situate it in relation to the surface environment to see its depth and volume, and to manage the associated risks.

Do BRGM teams use the scanner all over France?

Yes, we have two of them at BRGM now, and they travel all over France. Two of us do this work at BRGM. We walk underground in every region of France.

You spend your life underground.

We'll end up pale as a sheet after a while.

No, you're fine. You look good and healthy. Thank you for the information. Everyone at the Forum des Halles, come on down. It's really something to walk through these cavities. If you get a chance to meet BRGM around France, ask them to give you a tour with this VR viewer. It's fascinating. Thank you.

Thanks.

True or false: How can we explain the extinction of the dinosaurs?

Transcription

They're enormous, but not always, they're terrifying but also quite cute. We have a true/false quiz about dinosaur extinction.

Can I join the audience?

Yes, please go ahead.

SCIENCE LIVE!

TRUE OR FALSE

We've invited BRGM's Frédéric Simien to play with us. Let's get started. Shall we begin?

Yes, of course.

Here goes. First question: Dinosaurs have vanished. True or false? What does the audience think? We have a volunteer, look!

Is the mic working? What's your name?

Eli.

Eli, what's your answer?

Well, I'd say no. They didn't all...

They didn't all vanish?

No. Go on, explain your answer.

Crocodiles are dinosaurs.

Could we get an answer?

Are crocodiles dinosaurs?

They're reptiles but not dinosaurs.

But it was a good start.

Yes, he was warm.

Anyone else want to try?

Do you want to?

I think they have all vanished.

Are you sure?

Yes. We don't eat them?

They might be tasty, but no.

OK. And do you have any idea? You don't? Does anyone else have an idea?

Look, Fred, right there, another brave soul.

A brave soul!

I think they've vanished, but there are still animals, like sharks or birds, that descend from dinosaurs.

We'll need to clarify.

Let's answer first. Dinosaurs have vanished. True or false?

False. He's right. Birds descend from dinosaurs, even from theropods. I brought along a cast of a dinosaur print. This Grallator lived 200 million years ago in Lozère. You can see the three toes.

It's what family of dinosaurs?

The theropods.

Like the T. rex?

Exactly. But this one was about 2 m tall. So it wasn't very big. And it looks a lot like a bird's footprint. So you were right.

We agree that it's a different line.

Exactly.

There are commonalities, but dinosaurs as a line have vanished.

Exactly.

The big guys are gone.

OK. New species have recently been discovered. They're millions of years old. We're not sure if they're dinosaurs or if they're birds. Well?

Back in 2010, some discoveries were made in China. It changed our way of seeing things. Birds and dinosaurs used to be classified separately. But we studied their feathers and realized that dinosaurs' feathers weren't for flying, they were decorative.

Fossilised dinosaur feathers?

Exactly.

Wow! OK. So dinosaurs had feathers before they became a defining characteristic of birds.

Not all of them, but some had feathers. Thanks to pigments, we know what colour these feathers were.

From traces of pigment on their feathers?

Yes.

Which colours?

Take the Archaeopteryx, which is known as an ancestor of birds, we previously thought that it was light-coloured, but we realised recently that it was dark grey or black.

Totally black or with slight variations?

With slight variations. With some dark grey and brown.

Are there other physical characteristics common to both birds and dinosaurs?

Well, some are very similar, especially in terms of their pelvic bones. And we shouldn't say, "When hens grow teeth," because if we look back, dinosaurs had teeth, so birds must have had too. They have disappeared.

Any other questions on this topic or shall we go on?

Do you have a question?

No, I just want to say I'm a big fan of his.

That's not how we play this game! We're talking about dinosaurs. Next question?

Yes, next question. The second question: Were dinosaurs the only animals to vanish during that crisis, the crisis of extinction, let's be clear. So what do you think? I see Jean has a volunteer.

What do you think, true or false?

I think only dinosaurs vanished. No, I think...

You think it's true?

No, I think it's false.

OK. And why do you think that?

I think other animals died out too.

At the same time? OK. Fine, a first guess.

Anyone have a different idea?

Were dinosaurs the only animals to die out during the crisis?

I don't know.

Have a guess. Was it just dinosaurs? You were whispering, now it's your turn. Own up to it. So who else?

Whisper it to me!

Jean?

We have a volunteer. So, in your opinion, were dinosaurs the only animals to die out?

Yes, I think so.

True, false... it's a tie.

Does anyone else have an idea? We've had a clue. A minute ago, Eli mentioned crocodiles. And we said crocodiles existed in the age of dinosaurs. So they didn't become extinct.

Go on, you answered the first one.

They all became extinct, but other species survived, such as birds, which continued to evolve.

So some survived, that's what we said. But during the extinction were there others, aside from dinosaurs, that died out?

Did other species vanish?

No. I think the others adapted and survived.

OK. So clearly only dinosaurs became extinct. Another guess?

I'm torn.

Just have a guess.

It's either true or false.

I think other animals became extinct too. Why only dinosaurs?

Why only dinosaurs? Who do you think we are with your questions?

Shall we give them the answer? True or false?

It's false. Lots of other animals died out. We estimate some 65% of species died out. So many became extinct. There were well-known ones, such as ammonites, which looked like snails, and belemnites, and a whole lot of fossilised microscopic organisms, such as coccolithophores, which make up chalk. Chalk is an accumulation of fossilized microorganisms. Chalk is white. They died out when the dinosaurs did. So 65 million years ago, some 65% of all species became extinct.

And those molluscs you mentioned...

Ammonites.

Those are the fossils we often find out in the wild.

Especially from the Mesozoic Era, or Secondary Period. They're typical of that era.

Stroll along any Normandy beach and you'll find a fossil of a 65-million-year-old animal that no longer exists.

Exactly. I can show you a photo.

Sure.

We even have a photo of an ammonite. This book is all about the Secondary Period. Here's what an ammonite looked like in that era.

Like that. We'll show it to the camera. See that? It's a typical shape. OK. Let's go on to the next question.

We're waiting!

Sorry, excuse me! We were just chatting.

We're eagerly awaiting the next question.

Question 3: A meteorite killed the dinosaurs. True or false?

Look, Eli has an idea.

What's your name?

Pierre.

Pierre wants to guess too.

So, Pierre, true or false?

A meteorite killed the dinosaurs.

It's partially true. It might not have been the only cause of their death, but... There are lots of theories.

Come on, we need details!

Details?

Sure! What other causes do you have in mind?

Well, volcanoes.

Pierre's on the right track.

Stay right where you are!

I think Pierre is right.

There's a boy here. Where's the camera? What do you think?

I think it was either a meteorite or a volcano.

One or the other?

Yes.

We have experts in the audience.

I think it was just the meteorite.

You think it was just the meteorite. OK. Do you know the answer?

It was a meteorite that fell and was so huge it exploded.

Let's give the answer. A meteorite killed the dinosaurs. True or false?

It's false. It wasn't just the meteorite that killed the dinosaurs.

So, yes, but not only that.

Let's say it played a part. It hit about 300,000 years before the crisis. We think the crisis was gradual, it wasn't very diffuse. And actually, Pierre mentioned volcanoes. You should know that during the dinosaur crisis, there were massive flows of lava, about 4 km3 of lava covered the Indian continent. To give you an idea of the volume of lava, it would cover France twice if it were spread 1,000 metres thick. When you have all that lava...

A giant BBQ!

Exactly. It also changed the chemical make-up of the atmosphere, of the oceans, it provoked a lot of environmental changes.

So both contributed to their extinction. Is the next question linked to this topic? Let's keep playing. The crisis that led to the dinosaurs' extinction was the worst crisis the Earth has experienced. It was a major crisis. We said 65% of life.

Exactly.

It was a massive crisis. So true or false?

So is it true or false? I have a champ here!

Yes, it's true.

Go on, why?

Yes, because it destroyed everything on Earth.

Anyone else? Sir, don't pretend you can't see me.

No, but...

Was it the worst crisis? Go on, true or false?

True.

OK, let's see the answer.

Hang on, hang on.

The worst crisis is the one that's coming, the end of biodiversity.

No politics on TV! What you said is probably true, but that wasn't the question.

So, Frédéric, in the history of crises that we've seen up to now, was the dinosaur extinction the worst crisis the planet ever experienced?

Well, no. In the last 600 million years of the Earth's history, there were five major crises in all. Even before, there must've been other crises, periods when the Earth was frozen over. I won't discuss that now. But in the last 600 million years, of the five major crises, the biggest occurred at the end of the Primary Period, around 220 million years ago.

Could we have a percentage for comparison?

In relation to the dinosaurs, it was 95% of marine species, so it was greater, and 75% of land species.

That's huge.

It's colossal. It's interesting to see which species survived. There was a big reptile called the Lystrosaurus which survived the crisis. After that, it was the only vertebrate and accounted for 95% of terrestrial vertebrates. It was the only time in Earth's history that a species had no rivals or predators. As it wasn't picky about food, it developed, and it was the only period a single species dominated.

We'll go on to the last question of this first quiz. Humans have already encountered dinosaurs. True or false? This one's easy.

I have some experts here. So is it true or false?

It's false.

Never.

So?

It's false.

It's almost unanimous.

From what we said earlier, they existed very long ago. Anyone think the opposite? I think prehistoric people encountered them.

OK, we'll give you the answer. Is it true or false, Frédéric?

It's false. They vanished 65 million years ago and humankind appeared about 2 million years ago.

There's some 60 million years in between. OK. Great. But there are species that still exist today, which we've encountered, that encountered dinosaurs. We just mentioned birds.

Crocodiles. Tortoises.

Are there others?

In the ocean, there's the nautilus. It's known as a living fossil. It's the only one that hasn't changed since the fossil age. For 500 million years, it's one of the few animals which has never evolved survived the five major crises.

It's tough. Thank you, Frédéric, for all those answers. Let's join Axel at the science forum and continue this discussion. Axel, are you ready?

Absolutely. Frédéric Simien, let's open the forum together. We still have plenty of questions for you. You're a geochemist and managing editor at BRGM, the French geological survey. Geological and mining. To link our two sessions, why is the French geological survey interested in dinosaurs? I thought it studied rocks.

BRGM focuses on geology, which is quite vast. And rocks and fossils are closely linked because we often use fossils to date rocks. We tend to date rocks with isotopes now but fossils have been around forever. BRGM works with fossils too. We used them to demarcate the Champagne-producing region. Champagne grows with its feet in a geological period known as the Kimmeridgian. A town with land from that stage of the Jurassic period asked us to do a study to see if there were fossils dating from that time. They became part of the Champagne designation.

Without these traces of life, your work would be harder. Am I correct in thinking that the Channel Tunnel was built along the path of small fossils?

That's right, a microfossil called Rotalipora reicheli. There's a photo in the book. It's tiny. It was impossible to tell the two types of chalk apart. One is impermeable the other is permeable. The entire Channel Tunnel had to be dug in the chalk marl. BRGM made a series of boreholes to ensure it was dug in it. So it's thanks to this tiny creature found in rock of the same age across this region.

That we can cross the Channel.

Exactly.

When we look at rocks and try to unpack the past, to discover traces of life, what are the oldest forms we can find?

It's debatable. Some say 3.8 billion years ago, but it's hard to know if they're really signs of life. We only see little traces that we can interpret as signs of life or as mineral forms. So there's debate around that. Then, much later, around 2.1 billion years ago, there may be the first traces of multicellular life. Some people say it's multicellular life, others think they're artefacts, or mineral forms. There's a lot of debate. BRGM participated in the study of multi-mineral life forms from 2.1 billion years ago.

But you don't find forms resembling molluscs, do you? Everything is grey. Through careful analysis, do you conclude some molecules correspond to life forms?

The further we go, the more metamorphism there is. Metamorphism is a process of change in structure, texture and chemistry. So the farther back we go, the harder it is, because rocks have had a complex history.

Are there rocks that contain traces of past human life? I'm thinking of past civilizations or prehistoric people.

In Africa, there are footprints on lava that had not cooled. In Ethiopia, there are human traces from 2 million years ago.

Weren't traces of Roman lead found recently in some ice formations in the Alps?

Exactly, in an alpine glacier. We found traces of pollution from the lead Romans used. When it snows, ice builds up in glaciers and you get strata of time. From the Roman era, we found accumulations of lead.

So we're not the first to pollute the air on a global scale.

Unfortunately not.

Did they pay dearly for it? We're going to pay.

There was lead poisoning due to the lead pipes used for their drinking water, and many illnesses caused by lead.

Stand-up routine: What lies below our feet in Paris?

Transcription

Silvain Yart, Florian Masson and Hugues Bauer of BRGM unveil... the capital's subsurface.

SCIENCE LIVE!

Do you know what links these images? What links these images is the subsurface. Most of you came on the metro. So you've already traversed the subsurface, but we tend not to be familiar with other aspects of it. So...

That's right. Actually, there are over 2,000 m of strata beneath our feet, piled one on top of the other. The oldest of them are 250 million years old. When you dig under Paris, you run into different types of rock, from sand to gypsum, limestone, clay and chalk. I don't know if you know what they are used for. But if you look around, for building, we use sand for glass or concrete, gypsum for plaster, limestone as a building material and clay for tiles. Did you know that to build Notre Dame we used limestone from quarries that are now in the 12th arrondissement? The fire damaged some of the stones and they need replacing. They'll be sourced from Picardie. We couldn't have quarries in Paris today. In northern Paris, at Buttes Chaumont and Montmartre, gypsum was mined. Half of Paris's water is groundwater. The phreatic zone is the first zone we find underground, but there are deeper zones. Do you know what they look like?

I'd say an underground river?

No. Groundwater is contained in rock that is saturated with water, a bit like a sponge. So it's found at various depths. Under Paris, we bored 600 metres down into the sand, to find drinking water. And we made a discovery.

What?

At that depth, it is not only potable but warm too. 27 degrees, not hot for a spa. But in 1963 they had the idea of using it to heat Radio France. And thus geothermal energy was born. Today we dig deeper, up to 2,000 m, to find warmer water. It is used to heat whole districts and even Charles de Gaulle airport.

There are many uses for the subsurface. How long have we been using it?

The earliest uses date to the Neolithic Age, the period associated with a mysterious object, the first flints. And so they dug down to find flint. As time and the ages went by, needs changed. And as Hugues said, we needed other materials, limestone or gypsum, to build buildings. And over time we ended up with many abandoned quarries, and therefore many unused underground cavities. And above them, Parisians found ways to make use of them over the years. Whether it was legal... More or less legal, actually. In the 15th arrondissement, which isn't far from here, we find one of the earliest uses of a former quarry. It was turned into a troglodyte village. Homes were built in the quarries by carving cupboards into the walls. In some cases, they even dug chimneys.

You mentioned less legal uses. Can you tell us more?

For less legal uses, we'll fast forward to the French Revolution. At that time, some goods, like alcohol, were taxed upon entering Paris. There were toll gates where people paid a tax. To get around this, smugglers had the idea of using the kilometres of empty galleries under Paris to sneak alcohol in. So there was a giant game of hide-and-seek under Paris between the smugglers and the police. When the police caught smugglers, they would seal off the passages and the smugglers would move to a different area to keep avoiding the tax.

Were there other odd uses of the quarries after that?

Yes, after the revolution. We'll fast forward to the 19th century, the late 19th century. No, that isn't it. In the early 1800s, what we see here were born: the button mushroom. Underground cultivation was developed in Paris, between the 13th and 14th arrondissements. A market gardener named Chambry went down a quarry shaft in his garden one day and found a mess of button mushrooms growing on horse manure. He picked them and ate them. He liked them so much he stopped growing vegetables and switched to growing mushrooms underground. This tradition continued. And today there is a mushroom farm in Paris, but it's not in a quarry. Instead, it's in... the car park of a housing estate at Porte de la Chapelle.

That's awesome. Can we visit the subsurface?

Unfortunately not. The general public isn't allowed to go down into the quarries. But there is a place we can visit on the Place Denfert-Rochereau, and that's the Catacombs. They were built in the late 19th century to hold the bones from Paris's cemeteries, which were overflowing. They had to be stored somewhere, so they used pre-existing cavities. As I was saying, it's strictly forbidden to visit the quarries, except in a few places, for security reasons.

Speaking of security, Paris is full of holes. Isn't that a problem, Silvain?

It can be problematic. But fortunately, the cavities aren't all collapsing. In fact, you may have heard of the Clamart disaster. We have tools for studying cavities, such as this small scanner which enable us to create 3-D maps of cavities for risk assessments. But you have to remember that these cavities are part of our cultural heritage, and, as Florian explained, bear witness to the history of our cities. We must safeguard and protect this heritage. Today we won't take you to a real cavity, but come see us tomorrow, at our booth back there, for virtual reality tour of an underground cavity.

Silvain Yart, Florian Masson and Hugues Bauer, come join me at the Science Forum. We'll continue the conversation. Silvain Yart, you're an engineer at BRGM, you manage subsurface risks. You're the one who says not to worry, that it won't collapse on our heads or that we won't fall into a hole. You, Florian Masson, are also with BRGM. You're a technician dealing with subsurface risks. And Hugues Bauer, you're a geologist. You're the one who tells us which rock is which.

Exactly.

We don't have much time. I'm sorry. You were telling us about this. What is it used for? What did you say it was?

It's a 3-D laser scanner. It's a small object we take down into cavities, the former quarries that we can still access. It enables us to have a very precise 3-D model of the cavities, so we can assess the risks, identity the places where there's a cave-in risk, and if it's built up.

We'll project some images while we figure out how this works. You take this with you into the cavity. So you have to go down? The two of you take a lot of risks.

We only go down into cavities where we know we'll come out alive.

But you said, to know if it's dangerous, you have to use the scanner, so at some point...

There are some areas of a quarry where we won't go. You can tell right away if it's a no-go. When we see cracks in the roof or slabs on the floor, we won't go in, we ignore that part. When it's within range, we can scan part of a dangerous zone, but we're always very careful.

Here's an image, a photo of a gallery. So you hold out the device and walk along, and you collect lots of data about what's around you or what's beyond the walls? Can you see more than what's in the cavity?

It's just what we see around us. The device captures what we see when we walk around the quarry. It can't see through walls. If there is another gallery behind a wall, we have to go into it to see it.

So to use it, to map the subsurface, you have to go underground.

That's right.

You have a trace of everywhere you go.

Sometimes we spend the whole day walking underground.

It can take a whole day?

Sometimes. We might go down from 8:00 am to 6:00 pm, and picnic underground.

Hugues Bauer, do all of France's cities have subsurfaces that they have made use of for mining rock and building?

Absolutely.

Really?

All cities need raw materials for their development. They use the nearest sources. Usually, quarries are opened on a city's outskirts and continue underground. As the city grows, it covers the former quarries. There are quarries under Paris, which were used to build Notre Dame. As we saw earlier, they were often reused for other purposes. That's what makes it such a fascinating and historic heritage. Today, in the Paris and the Ile-de-France area, there are 100 quarries providing building materials.

We heard that Florian and Silvain trek underground. Do you go into the quarries too, the former quarries, to take samples or conduct research?

Absolutely. The quarries are ideal places for observing rocks in a pure state. So geologists tend to carry out surveys and take samples from them. You should know that Paris, or Lutèce, as it was called, gave its name to a geological era, the Lutetian era, whose stratotype is found in Paris's underground quarries.

Something is happening back there, at the BRGM booth. We can take a virtual reality tour thanks to your underground treks. We put a headset on. Will virtual reality be used more and more to study the 3-D world underground? With a map, you don't get the depth. Silvain Yart.

We're making increasing use of this technology. As for its scientific use, it's still early days. But for raising awareness and sharing information with the public, it's an extraordinary tool. Since technically the subsurface environment is not open to everyone, we can bring the subsurface to the surface and show a maximum of people what we see. That in itself is extraordinary. But for now, it's more about the heritage and protection aspects than purely scientific ones.

Thank you all for telling us about your life underground.

Gigantic asteroid impacts (more than 10 km in diameter) in Mexico, colossal volcanic eruptions in India (2.5 million km3), etc. Apart from these cataclysmic events that stick in people's minds, there are also other environmental developments that need to be considered, on another time scale, such as sea level variations. In fact, sea level decreased significantly towards the end of the Cretaceous period. The same is true of global temperature. And dinosaurs are not the only species that disappeared.