Sustainable and secure access to raw materials is fundamental for all EU industries and is a necessity for the green and digital transformation of its economy. According to the OECD, raw material extraction has doubled since 1990 and global consumption will increase by 40% by 2040 and by almost 90% by 2060 compared to 2017. Global raw material supply chains will come under severe pressure, testing their resilience, and EU industrial ecosystems will face increasing global competition for resources.

Metals and minerals are products that are part of our daily lives. As European industry moves towards climate neutrality, dependence on available fossil fuels could be gradually replaced by dependence on non-energy raw materials. Geographically speaking, the production of these commodities is often more concentrated than that of oil or natural gas (both for extraction and processing).

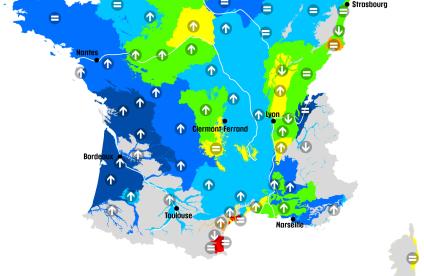

The EU is well supplied with industrial aggregates and minerals as well as some base metals, such as copper and zinc. It produces only small quantities of critical raw materials, although the potential for some of them is significant.

Supply vulnerabilities and dependencies

The most economically important raw materials with a high risk of supply shortages are called "critical raw materials" by the European Union. They are essential to the functioning and integrity of a wide range of industrial ecosystems:

- rare earth permanent magnets are used to power electric cars and wind turbines;

- magnesium is used in lightweight aluminium alloys for vehicles and construction;

- silicon metal is used in semiconductors;

- platinoids are used in hydrogen fuel cells and electrolysers.

In 2020, the EU identified 30 critical raw materials. For example, over the period 2012-2016, China provided 98% of the EU's supply of rare earths and 93% of its magnesium, Turkey 98% of its borate supply, and South Africa 71% of its platinum and even more for platinoids (iridium, rhodium and ruthenium).

The analysis of the EU revealed its high dependence on imports of raw materials for key products and technologies. For example, the EU supplies only 1% or less of specific raw materials for lithium-ion batteries, wind turbines and electric motors.

The Commission has also analysed the future demand for several raw materials, which is expected to grow strongly in various sectors and technologies, including renewable energy and electromobility, digital, defence and aerospace.

Geosciences no. 26: Critical metals, can ethics and sovereignty be reconciled?

Issue 26 of the Géosciences journal, published in June 2022, focuses on the topic of critical metals.

The energy transition towards carbon-free production reveals more than ever how dependant our technologies are on an increasing amount and variety of metals. Will we be able to meet all the needs for mineral raw materials in the coming decades? How can we secure our supplies given that the last mines in France closed at the end of the last century?

BRGM, France's leading public player in the field of mineral resources, has devoted this issue of its journal, Géosciences, to answering these questions and many others.

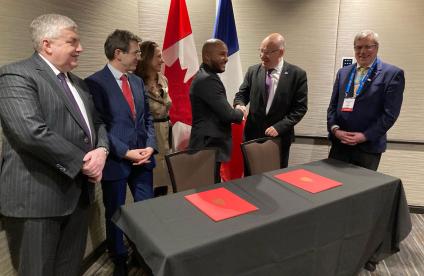

This issue, which includes an article by Philippe Varin, author of the recent report on securing the supply of mineral raw materials to industry, and an interview with Christel Bories, CEO of Eramet, discussing the place of metals in our daily lives, takes stock of European mining potential and reviews the state of recycling in France and the prospects for innovation in this field.