100 years of coal mining

Transcription

Sound and Light Productions and Pierre Long present

100 YEARS OF COAL

Filmed in Lens (Mines 14 and 15) with the active involvement of management and staff via an initiative by the coalfields of the Nord and Pas-de-Calais.

100 years of coal, and the town of Lens has spread in all directions along with its mines. All roads here lead to coal. And alongside these roads, a huge number of houses have been built. The history of Pas-de-Calais is closely linked to coal. From east to west, for over 100 km, the black strip of the largest coal seam in France is now one vast conurbation. The names of the villages change with each pit, and over a million people make their living from the black treasure. The history of Lens is the history of coal, 100 years of coal. 1852. 1952. A century is stored here, within this strange library, where each book tells the story of a man. We found, amongst all the others, the official record of the oldest living miner.

Louis Delattre

Worker's Book

His name is Louis Delattre. Born in 1867, he started work underground in 1879, aged 12. He left for another adventure on 3 September 1914. As he was loyal, he returned to follow his destiny from 1920-1925. After 41 years' service, Mr Delattre still tends his garden. He never expected that one day he'd be the guest of honour at the centenary of a mine his grandfather helped dig. In the changing room of his old pit, where the men looked forward to his visit, Mr Delattre donned the white outfit worn by miners in the past, as if, at a time when conquering the earth was struggle in darkness, man wanted to take a bit of daylight with him. With the former miner, the men laughed and joked, but they hid, behind laughter, one of those emotions that is never shown here, and that modesty hides among the strong. Whilst teasing Mr Delattre, they showed, once more, a remarkable solidarity and deep respect for the profession. And now the descent. The real journey. The moment when even the most accustomed are aware they're doing something exceptional. Louis Delattre, watching the light disappear, descends into darkness and into the great unknown, looking to rekindle memories. But of Mr Delattre's memories, nothing remains except the coal and the men. Everything else has completely changed. The din is huge, as are the machines. Strange vapours rise up out of the noise from the mechanical tremors of steel around a new miner, a technician, in charge of the machine. Louis Delattre's memories are of a narrow gap where, doing as he was told as a young, barefoot boy he collected the coal in his wicker basket. Harvesting coal from the carbon tree. A slow, laborious progress. Scraping away with a pick in the faint light of an oil lamp, a smoky oil lamp from which you lit your pipe. Never mind the naked flames, the bare hands and chests. Such nudity was met by an adventurous spirit worthy of explorers and founded on pure courage. Underground agriculture where horses pulled the load, as in the fields. A time when today's atavisms were created, traditions were built. Men with handlebar moustaches, Jules Verne characters at a miners' meeting, descending in a barrel or crouched in a truck. Old memories, old people, faded photographs. Women with large busts and long skirts. And a horse to pull, push, cart and perform acrobatics. Mines that didn't dare proclaim themselves or that, on the contrary, adopted all the fads, like the Galerie des machines or the Trocadero. Old ledgers conjure up yet more. Daily salary: 3.25 francs. 4.50, 2.60, 1.75. This man had a debt of 27.25 francs. "Temperamental". "Left for America". And this one "didn't get along with people". He preferred the harvest. A deep scratch at the bottom of the page makes the point. And now we remember the damage caused in 1916 and 1917 by German bombs. Lens and its mines were razed to the ground. Attacks and counter-attacks made the region the scene of a fierce battle. The pits were demolished, blown up, flooded. After the Armistice, when pumped, a volume of water equivalent to the Seine in Paris was extracted in just two weeks. It was all rebuilt in a desire to forget the previous destruction. Life could not restart without coal. The miners, always first in line, went straight back to work. Lens, destroyed and rebuilt, was a symbol. All along the coal seam, in reaction to the destruction, the building fever added to the patchwork of northern mines. Who hasn't heard of these famous names? Valenciennes, Douai, Hénin-Liétard, Oignies, Liévin, Béthune, Bruay, Auchel. 1945, the tireless miners went back to work. It was time to modernize. The nation had taken over the future of this key industry.

Hundreds of thousands of workers would turn their efforts to one goal: French coal, of which the coalmines in this region supplied the majority. To make more electricity, power stations were built, producing billions of kilowatts. The recollection of these memories brings us to the present. Mr Delattre's dream has been realised in the most convincing manner. Miners haven't changed, and nor has the humour, but the developing technology has made these men the masters of ever greater forces. "A bit brutal at my age. My arms aren't used to it." "But I can still get down on my hands and knees." The young miners, proud to give an old general a tour or their battlefield, patiently explained. The coal is put on this conveyor belt, which runs along the vein. It is then picked up by a second, faster conveyor belt. A mine, today, is kilometres of rubber belts carrying coal. The stream gets bigger and bigger. Once outside, other belts cart it away. But you can't just extract the coal, you have to support the roof as you go: previously with wood, now they use steel. After eight hours, natural forces are allowed to take over. Each recovered steel pillar is used further on, and from one colonnade to the next, the coal cake is eaten away. As for the conveyor belts, which can be 100-200 metres long, they are moved with compressed air, it's that simple. The cycle of operations starts again in the hands of the next crew, who, as you will see, Mr Delattre, do not mess around. There: some well-placed powder does a great job. The conveyor belt is fully loaded. The rest, shaken by the explosion, is attacked with pneumatic drills. When, in a mine, all sections are extracting coal at the same rate and you see all the output being carried from gallery to gallery, you can imagine how many hundreds, thousands of tonnes are produced every day. The final torrent is stopped by a man who controls the flow with a tap and loads the small trucks. That's how the first coal trains are formed, underground. Louis Delattre, who wanted to see everything before going up, no doubt for the last time, stopped here to have it all explained to him. He will have gleaned as many new memories as he brought back for his grandchildren from his campaigns. He deserved this tour, to be able to compare the past and the present. Between the pioneers of the past and those of the technical era, he's an indissoluble link. They have the same virtues, qualities and birthright. Since he's unaware of modern science, he takes out his pipe and tobacco pouch. He was told doing so was no longer permissible and was given a regulation chew, which he didn't like at all. But Delattre is indulgent. He smiled, smoothed his moustache and had a snack.

Miners of France

Transcription

MINERS OF FRANCE

24 August 1944. Whilst the enemy, hunted in every village in France, tried to get back to their lair, tanks, announcing the liberating forces, entered the capital. Everyone who lived through this historic time felt the liberation of Paris meant the end of France's misfortune and the start of a new golden age. Sadly, the joy was short-lived. The toll of the war and the occupation risked replacing the general euphoria with despondency. Heading for ruin, France issued an appeal.

France needs coal to rebuild.

Miners! France's fate is in your hands.

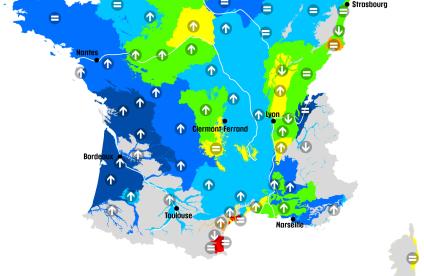

Before an attentive audience, parliamentarians and union officials asked mine workers to respond to the huge needs that the country's recovery made pressing. Appeals were made to 320,000 miners spread across France's nine coalfields, which would be nationalised to concentrate their efforts. They started with the Nord and Pas-de-Calais, which represented 60 percent of national production, and Lorraine, which could reach 25 percent. Across the vast pitheads of the Nord, at the bottom of the shafts dotted over the Lorraine landscape, in the coalfields of Blanzy, the Loire, Aquitaine, Auvergne, Cévennes, Provence and Dauphiné, the SOS was heard. Lacking the materials to provide workers with sufficient mechanical equipment, they used all available means, and even resorted to worn and outdated equipment. You could even see, pulling a string of wagons along the galleries, the old pit pony, which was becoming extinct. Despite their inadequacy, in the hands of brave and tenacious people, these resources gave industry the initial push which it needed. Chimneys once more spat out plumes of smoke as factories started up. The machine was in motion. French miners were proud and honoured to have kick-started the reconstruction. But getting back to work wasn't enough; they had to make urgent repairs to increase coal production. With an incredible team spirit, engineers and workers worked together to rebuild the ruins caused by an enemy who, in Lorraine especially, left a trail of destruction. The coalfields refurbished their installations and built new ones. Measures were taken to increase volume. They concentrated on boring new shafts, a difficult and delicate undertaking, since some shafts can be up to 1,000 metres deep. They looked to increase productivity by organising apprenticeships and accelerated training programs. In addition to theory, there were practical lessons: first above ground, setting it up to look like a mine, then at the coalface itself. The young apprentices learned the skills of being a miner. Special classes were designed for adults who needed to adapt to the new working methods. What are these new methods? What does a modern mine look like? What life does a miner lead today? We'll find out during this visit. In the ground, coal forms huge seams covering several hundred hectares. They are relatively thin and separated by rocks. To extract the coal, two shafts are dug vertically through the seam. The two shafts intersect at different levels with the horizontal galleries, which are tunnels dug out of the rock. A ventilator at the top of one shaft draws the air coming from the other shaft to clear out noxious gases. Wagon trains run along the galleries, transporting coal to the lifts. Where the galleries intersect with the seams of coal, other, smaller galleries, called passages, are dug. The problem is removing the coal contained between the upper and lower passages. As this diagram shows, the coalface progresses through the layer as the coal is removed, or as they say, extracted. It is removed via the lower passage, as shown by the arrow. To understand how coal is extracted, we're going to follow one of the teams. The miner and the mine have been transformed. The old pick has almost disappeared, replaced by a pneumatic drill which gives a much higher yield with less effort. The pneumatic drill itself will soon look old-fashioned, and be overtaken by more modern and more powerful equipment. This machine is an electric coal cutter. This diagram shows how it works. It's just a circular saw equipped with shark teeth, which cuts into the base of the coal face and, moving all the way along, makes a deep groove in the coal. A single worker operates the machine, which slices easily through the coal. Once the coal cutter has done its work, the remaining coal is extracted with explosives. Having been extracted, the coal has to be removed. This gigantic lobster claw grabs chunks of coal using a circular motion. It can grab 3 tonnes of coal per minute. The machine requires minimal personnel to be operated. The coal is disgorged by the loader onto a conveyor belt, which quickly transports it from the coalface to the loading point. At the loading point, the coal is poured into carts which can hold 3,000 litres. The carts move automatically once they're full. Trains are formed, coupled to a diesel or electric shunter, which moves them through the passages and galleries. Their horizontal journey ends at the station situated at the bottom of the shaft. Still moving automatically, each cart goes into one of the cages of the huge lift, which will take it to the surface. They arrive above ground. Each cart is emptied by being rolled over by a huge barrel. Once emptied of its contents, the carts pass over a points system, which we will follow. Everything here is automatic. One specialist manages the whole operation. The carts are sent to the cages to go back down, starting the cycle once again. Electrification and the mechanisation of extracting have revolutionised mining. There is more specialisation, and often, the miner has now become a technician. The faces of these men no longer evoke the wretched struggle which was the lot of miners previously. It's no longer an antique lamp which they hand in, but a modern electric lamp, a headlamp, as they're called. Before taking a shower, the miners remove their work clothes, hoist them up and padlock them. An ingenious and practical system which prevents swaps, intentional or otherwise. A miner's life has long been considered an austere and joyless existence. It was true in the past, but great efforts have been made to make it more cheerful and not only decent but also pleasant. A miner has the right to enjoy the tranquillity of home. And like Candide, he can cultivate his garden. New estates are being built around the major coalfields. These are not gloomy and forbidding estates, but cheerful and harmonious villages where workers can rest and relax. Across the country, 45,000 new buildings are planned. Now for the question of supplies. The physical exertion of working underground isn't possible on an empty stomach. The tour of the central cooperative, run by staff representatives, is reassuring. It has, besides a butter factory, a liquor factory and a roastery. Several shops and warehouses are reserved for clothing. The miners' cooperative works every day to improve living conditions. For example, supplementary rations are often provided to feed large families. Clinics, hospitals, maternity wards: The mining world, with its admirable solidarity and team spirit, can only be at the forefront of social movement. We've lost count of the number of holiday camps opened for miners' children. But the miners themselves should also enjoy the fresh air. Activities are organised for their benefit, but they can also enjoy an affordable holiday in a holiday resort. Each year, the Château de La Napoule on the Côte d'Azur, with its granite keep overlooking the Mediterranean, sees a crowd of miners and their families who come to enjoy the Riviera. Enjoying a holiday, playing sport. Miners are athletic, as witnessed by the number of football teams established in mining areas. Some, such as RC de Lens, Olympique d'Alès, Valenciennes, Douai, etc. compete nationally. Isn't industrial activity like a sports competition? In the daily struggle to rebuild France, where recovery depends on regaining its former health and strength, the mining team has scored the most points. How could it be otherwise? Coal is the heart of the French economy. Industry depends on coal production. Electricity production and transport are dependent on coal, and normally represent 3/4 of the total energy used in France. How could a miner not feel proud of what he represents? Aware of his responsibility, be he engineer or young apprentice, he knows he's part of a huge national project. He can smile and face the future with confidence, as his tenacity and the importance of his work make him the leading worker in France.

The men of the night

Transcription

The Night Workers

Executive Producers

Son et Lumière and Pierre Long

Directed by Henri Fabiani

Director of Photography

Jean Isnard

Cameraman

Jacques Klein

Gaffer

René Braconnier

Music performed by

Lorraine Basin Coalfields

Woodwind Ensemble

Conducted by P. Semler Collery

Narrated by Serge Reggiani

Sound Post-production

SIS

Sound Engineer

R. Lion

Production Studio

L.C.M

Thanks to the management, engineers and miners of the Lorraine Basin Coalfields, without whom this film would not have been possible. This film follows the men's daily lives without special effects.

It's 5:00 a.m. and everyone is asleep. There is no sundial on the colliery buildings, as these Lorraine miners expect nothing from daybreak. Neither does this limping man. His story is a simple one. Twenty-six years in the mine, one leg gone, on the road to nowhere. Now an instructor, stuck on the surface. He suffers from what they call pit malaise. He has loyal friends. But it's not that easy. We don't like being pitied around here. So, think long and hard.

Today, the kids are going down the mine for the first time in their life. Fate chooses you to teach them.

What's one more trip down the mine? But he must content himself with a model. Sometimes a man's story is simple and needs few words. A word to those above and he can go down. Baptism of the pit. But where are those blasted kids and who are they? Three knocks on the door and five little faces appear. One, two, three, four, five.

Like you, they've been waiting. The team. The six adventurers. Six companions begin their journey. Six companions reach the locker rooms to don the uniform of this sport. Their night clothes. A patchwork of fabrics and colors. Trousers that seem dirty when clean but better when black. The cap, called a barrette in French. That's what a man wears at 14, a prestigious uniform. Are they real kids or real men? Real tomfoolery either way. An incredible adventure is afoot. We remind you that for safety reasons... No smoking kid, no smoking! One more accessory, the lamp. The only light permitted. A regulation lantern whose light guides them through the night. For the boss, an additional lamp: the safety lamp. An open-flame lamp because where there's light, there's life. A friend wishes you a safe journey. Do you remember your first descent? They, too, will remember theirs. 100 meters, 200 meters, 300 meters, 400 meters, 500 meters, 600 meters, 700 meters, the bottom. The night. Not everything here is horizontal. There are also inclines, and steep ones. It's impressive, scaling 90 meters of shaft at a 90-degree angle. It's a real climb. A very steep climb. And we kids think it's kind of fun. At the end of the shaft, at the end of the night, the climb leads them to the coal. Here at the end. Coal sleeps upright here. That's why the climb was so steep. Do you see what I mean? Make a hole in the roof of coal, and you can manage to climb up by clearing a new floor underfoot. The ground is covered with sand from outside. The sand is mixed with water to flush it down. 700 meters below, this slurry splashes into a strange lagoon, thick and troubling. The coal is disturbed and escapes. Water trickles down, seeking unknown oceans, while along this hydrography the men walk... and walk tirelessly. When the path ends, turn right. The scenery changes, but perpendiculars remain illusory. At least for this tipsy lantern. Just like a ship that heels, the seam inclines. Look. Petrified by a tremor, it lay dormant for 20 million years. The coal is startled. I found you, you're mine now. The words of men. Look. Listen to this monster that bites relentlessly. This is the steel woodlouse. It weakens the foot of the wall, which explosives then break up. Then, the tireless monster will extend its claws to pick up the pieces. Watching this mechanical miner, you remember the artisan you once were. You pulled black rock out with bare hands. Well, almost. And you rolled it on up. Well, almost. If needed, you would've carried it on your back into the daylight. Nature cannot stand emptiness. Faced with her overriding power, it is wiser to back down. This is called block caving. A trustworthy technique. This is a place that marks memories. Waterfalls, eddies, waves and confluences. Run, run, languorous stream, black river. Your water... Your heavy water leaves its last shimmers here before fading in the intrepid daylight. Here are the keeps of these extraordinary estates. Château de Lorraine. Faulquemont, Merlebach, Wendel, Sainte-Fontaine, Simon, Gargan, La Houve. Forty towers, forty metronomes in perpetual motion, beating the infernal rhythm of the black rock's absurd dance. A country was built around it. Houses. Machines. Communities. And smoke. It breathes via this overhead giant. The lungs of the mine. The giant heart below draws its oxygen and sheds its blood. Constructions that shatter the human scale. 9 tons per minute. 12,000 tons per day. Boastful figures. The machine is impervious to this. It reacts to smaller things: two fingers on one hand are enough. Two fingers to make, via a cable, 9,000 kilos of coal roll toward its great adventure. So begins a strange kind of dance to the sound of a beating drum. Here is the washer to clean off all the dust gathered on the way. You cannot go to a dance dirty. Small here, medium ones there, big ones forward. It's noisy. Then all is calm and silent. Until a cymbal crash marks the arrival of the black rock. It will erupt into its fleeting existence. A stone for power, heat, coke or gas. A controlled fire. A standard blaze.

If you want to be happy Take life as it comes Down the mine There are no questions Take away music And you have no song Take away miners And the coal is gone

On the path of the unknown, nothing should stand in man's way, and so the mine lives on. Here, where there is more sand, history is being written with great quills.

If you want to be happy Take life as it comes Once daylight you view There's nothing to do Take away music And you have no song Take away miners And the coal is gone

A friend standing on the platform is waiting for him. They exchange a few words. Nothing much. Do you confide in people? Not these men. That's all.

The End

Period film taken from the Charbonnages de France library and re-published in 2006 as part of the DVD entitled "Planète charbon. Une épopée, un héritage" (The world of coal. An era, a legacy) (date unknown).