Erosion of the Var coastline: EUCC-France workshop

Transcription

The issue with this type of coastline is that while very appealing, it is also fragile. How to reconcile environmental protection while maintaining its appealing nature? But the million people who visit every year must not be allowed to destroy what draws them to it. That must be reconciled. It's the general problem with sustainable tourism.

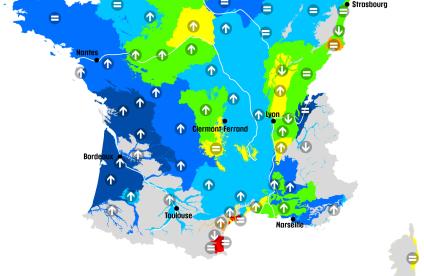

I'm happy to be here today for this vital work in the field inasmuch as you have associated, I'm pleased to say, coastal erosion of beaches with the erosion of cliffs. These are key issues for the region, and it is important to note that global studies remain key, along with studies linked to hydro-sedimentary cells. We are working on a regional vision of how the coastline will evolve. Today, I think we'll be able to see some of the problems affecting 4 towns.

During this workshop, we'll discuss the problems of marine erosion. We will also discuss the rather insidious dangers, seen only by the trained eye, of cliff instability.

On the coastal path, the proximity of the town brings problems every year. It costs about 1.5 million euros annually to restore the sections of pathway that disappear. We've sometimes wondered whether to leave the pathway where it is and continue to invest 1.5 million or move the pathway.

We are going to listen, exchange ideas, discuss, and make suggestions. That's the aim of these workshops.

A quick geological review: we are west of the Maures Massif, a crystalline rock formation that has been metamorphosed by high pressures and temperatures. Around this massif is a Permian depression, the result of erosion in the initial Maures Massif, which was much higher at the time. We see formations of alternating arkose, mudrock and sandstone in the cliffs here in front of us surrounding La Coudoulière beach. The issue of coastal cliff erosion can be seen in this instance by the difference in materials between the hardened levels of sandstone and softer levels of clay, meaning erosion occurs in the softer clay causing what is known as differential erosion, with the changeover of blocks, depending on the rock stratigraphy, which creates an overhang and destabilization of the cliff.

When we look at changes in this coastline, just in terms of the changes in the shore, we see great stability, with the rate of evolution being a matter of some uncertainty.

The nature of this site meant that once the Coastal Conservancy became owners, we worked alongside the local authorities to set up a management plan in order to outline management interventions on this site over the next 10 years. Until now, management plans were limited to Coastal Conservancy properties, but in the context of the overall management of coastal areas and the backshore here at La Coudoulière, we wanted - and the town agreed - to expand the limits of the management plan. So far, these operations have not yet begun, but the intention is to eliminate and move back the parking zone where we are parked, here on my left, and gradually clear rocks from above the beach. As Alexis Stépanian specified, we have a relatively stable beach and coastline that has nevertheless been disturbed by landfilling works. We are on landfill that has reversed the natural bend of the beach. Today, as we can see, the beach is progressively taking its place, and the coastline will gradually return to a convex shape in contrast to this hollowed-out shape.

I want to talk about a study on the link between erosion and vegetation carried out by the Forestry Board (ONF) in conjunction with the BRGM. The objective is to highlight areas influenced by vegetation to see whether these zones might require special erosion management linked to vegetation management, and whether in those zones revegetation work or biological engineering might be appropriate. In the case of trees, what's hugely important is the external vegetative part, which has a major effect in terms of providing shelter from rain, intercepting and limiting the phenomenon of water running down. It must also be borne in mind that trees can have a destabilizing effect. Take this tree for example. Until now, its roots have served to restrict coastal erosion here. But given its position, it's easy to imagine that one day it might have the opposite effect by falling and destabilizing a large section of this area.

The Bay Contract came about in the '90s after bacteria levels raised questions about the quality of bathing water and shellfish production in Lazaret Bay. The Bay Contract is a local plan of action for application of the European Water Framework and Marine Strategy Framework Directives, along with the SDAGE action programs. Locally, we organize actions on Toulon harbor, with all the harbor stakeholders. We've seen a sharp improvement in the beaches and bathing-water quality. All beaches are now classed as excellent throughout Bay Contract territory. We've also set up a decision-support system in the management of water quality with rapid analyses. Instead of microplate analyses, which give results in 48 or 72 hours, we have rapid analyses in 3 hours, allowing us to react quickly to suspected pollution. We currently have suspected contamination in one sector, in a 10-cm band, with spikes in pollution for contaminants - mercury, lead, etc - collected during the scuttling of the fleet, in the war. Unfortunately it isn't deeply buried. During a storm, or when a large ship passes through with large dredging propellers close to the sea bed, sediment becomes suspended in the water again.

Here is where we decided to review the VALSE research program to help companies facing coastal cliff erosion in the PACA region. The objective of the project was to work in an interdisciplinary way across human and geological sciences. The idea was to quantify erosion on coastal cliffs, go beyond the simple hazard previously identified, evaluate the occurrences of cliff landslides, qualify human behavior in terms of use, presence and management, and improve knowledge while helping with coastal territory management.

We've monitored it over 80 years. The average contraction rate - bearing in mind that the average is not representative of each event - is something like one millimeter a year. We looked at the type of forcing, too. We talked about it earlier. Is the main factor the sea or is it meteorological action, i.e. rain? How to characterize the action of the sea using aerial-view geodata? Hence the idea of using a methodology that allows us to look at the cliffs from the front. This allows the cliffs to be scanned by boat. The system gives us a 3D scatter graph, plus a set of photos, allowing us to examine the geology and identify points of erosion. This meant we could directly identify patches of erosion and pinpoint them over the entire area studied.

Tourism can make it difficult to preserve biodiversity. In general, we manage, through management plans and movement. Some particularly rich areas are protected. That's not the case here, but we do it on some sites. Being open to the public raises safety issues. The work carried out here had major safety considerations, since we had observed pebbles and rocks falling from the cliff onto the beach. This produces an additional problem as the beach is extremely busy in summer. Our thinking was triggered by two studies: a geotechnical study to examine the soil and see how to do the work. Also an engineering study, for which the National Forests Office won the contract, to consider which techniques to use, given the sensitivity of the location: gentle techniques to preserve the environment.

We were rightly instructed to leave the screen protection and fix it up above so as to optimize it, which is what we did. We also tried, in addition to managing maritime erosion, as we have seen this morning, to manage the surface runoff that might fill the embankment with water, which slipped in 2008. This amounts to a wooden box filled with materials from the site. We have in this way limited the amount of exogenous materials needing to be brought in. It is a freestanding structure of no little weight which aims to 1) withstand pressure from the upstream bank and 2) protect the foot of the slope from marine erosion. We increased safety by fitting wire mesh to hold back stones, and stones to hold back the smaller stones behind, plus a geotextile along with materials from the site.

We had to integrate into our thinking the way the cliff/beach system works in the same way a dune/beach system works. Every time we cut off a beach from dunes, we are heading for trouble, so bear that in mind.

I agree with the idea that, as far as possible, natural habitats should be left to evolve by themselves with minimal intervention. We always return to the same conclusion: we have conflicting interests, which are: nature, on one side and on the other, the need to welcome visitors, to corral them and control their movements.

This sensitive natural area now belongs to the département. No elected official accepts... Cliffs will collapse, that's the reality, they always do. In sensitive natural areas, we have coastal cliffs, inland cliffs, with holes, chasms... everything. We know the issue. But no elected official would allow a cliff to collapse and endanger people.

The difficulty here is that the rock is particularly spoiled, and there's a lot of vegetation cover. Quite a few landslides have occurred on this site. One particularly infamous incident occurred in 1976 at Pin de Galle.

A word about the beach's geomorphology. As you see, this is coarse sand, it even has some gravel. It's an unusual beach on this coast and an iconic one, a pocket beach at the bottom of a headland. Interestingly, it hasn't been subjected to massive reloading-type changes. The measurable rates of change make us relatively confident. Rates of evolution since 1920 have been around 0.2 to 0.3 meters per year. So while the ground is rather stable, the prospects are not good... given that it is shored up by the erosion of the cliff behind. This beach has deposits - you are standing on them - of posidonia: deposits made up of debris from the seagrass bed further offshore which makes up...

An underwater forest.

An underwater forest, the lungs of the Mediterranean in terms of biodiversity.

From the '70s and '80s, protection systems had to be devised. As Mr. Stépanian just told you, the site is constantly eroding without its supply of sediment now diverted to other parts, and with the Salins channel and the road. The first consolidations made used rockfill with wooden piles, really hard materials, which weren't altogether effective. A lot of thinking was required to manage this tombolo until 1996, when a storm destroyed the road. This road is a second road. The first one, further up, was destroyed. The dunes are often destroyed by storms. In terms of management, the town tries to reform them as naturally as possible. We bring in sediment mixed with stretches of posidonia recovered from the beaches in the spring.

We tried to compensate for erosion using riprap and spikes on the Ceinturon road you can see there. We had a system that was naturally balanced, but which became imbalanced as a result of works.

For several years we pumped the sand accumulating in that area to bring it back here. This is the most sensitive erosion spot. As solutions go, it isn't conclusive. Erosion is ongoing. In 2010 and 2012, the town undertook studies to define the work. Two main possibilities are open to the town. Either we carry on with the breakwaters we see further north, making our line of breakwaters with small cavity beaches to the port of Hyères, since the port of Hyères is a cell. Or we elaborate our thinking and imagine the site another way, the idea of rebalancing the beach with a dune. But that involves encroaching on the road. We have considered the issue of submersion. We now know to expect a rise in sea level. As you see, the land is flat. Further up, outside Hotel Le Plein Sud, is a small marsh. We wonder, given the current storms, how far the water can go. By 2100, storms will bring a 60-cm rise in sea level. How far will they go? It's a good question.

Thanks to all the organizers for showing us around. It was excellent, very interesting. I've learned a lot. Please give them all a hand.