Organised by the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation and 13 research facilities, in partnership with L'Esprit Sorcier and with the support of the CASDEN bank, the "Science Cabaret" took place at the Cité des sciences et de l’industrie (Paris) from Friday 5 to Sunday 7 October 2018.

"Science Cabaret": a stand-up routine about soil decontamination using bacteria.

Transcription

Hello.

Hello.

See this pretty picture, Hubert? Any idea what it is?

It doesn't look like much. Maybe traffic in the rush hour?

Automobile traffic? No. They're bacteria. Do you know what bacteria are?

Not really. They don't have a very good reputation. I associate them with serious diseases.

We often associate bacteria with disease. But bacteria play many other roles. In humans, they have a positive role in the digestive system. We need the right amount of bacteria inside us. But bacteria do not only act on the human body.

They are active throughout the environment. That soil... Did you know that one spoonful of it can contain more than a billion bacteria?

So my jam jar contains as many bacteria as the entire human population of Earth? But what do they do in my soil?

In soil, your bacteria are active in recycling organic matter. For example, when leaves fall, they are broken down,

shredded by insects. Fungi and bacteria take over and degrade the organic matter, instigating the cycle of organic matter.

Like my garden compost, it's full of bacteria.

Yes, bacteria play a huge role in the environment.

They do a lot of other things beyond your soil. Bacteria can even break down pollutants.

That's interesting. If they're plentiful, fast and cheap, I reckon I can hire them.

What is it you do?

I study polluted sites and I help clean them.

Why? What is a polluted site?

I need to tell you a story. I'll keep it brief. Once upon a time, in France, there was a polluted site, about 150 years ago.

It dates back to the industrial revolution, when factories and mass production first appeared. Many factories were located near city centres. Large entities but also small business activities: service stations, garages, dry cleaners.

And gradually... Here, we see a service station, with a nice big patch of fuel. These sites appeared within cities.

Cities keep on expanding. So they moved out, either to the outskirts of cities or even to other countries. When we have 150 years of history, we leave traces in the soil and in the earth. We now need to monitor these sites. Like when you have an oil tank that springs a leak, it leaves hydrocarbons in the soil. A few years ago, we didn't have the waste-management practices that we have now. Don't think that all these sites are polluted. 25 years ago, we began to list them, to identify them. We also try to monitor them. All this attention and concern is linked to our increased awareness of the need to protect the environment. A few years back, waste management was not the same.

Now we sort waste, and we have rubbish dumps. We think of ways to reuse it: the "circular economy". It's a dynamic environment we're still learning about.

In terms of pollution, what kind of pollutants are you talking about? Which ones are most prevalent?

The public can help us. You may already know about pollution or pollutants. Any ideas? Not necessarily.

Maybe metals or hydrocarbon waste from oil?

Not bad. There are different categories of pollutants, large families of them. The pollutants we treat most are the metals: arsenic, chromium, cadmium, lead. There are plenty. For those who know the periodic table, they are all in there. Then there are the oil-related products: petrols, oils, fuels, which are also a large family of pollutants.

All that along with the chlorine family accounts for 80% of pollutants in soil.

Are many sites affected by these pollutants?

It's a delicate issue, but yes. France reflects the situation worldwide. We have a few thousand polluted sites in France.

To get some idea of what it represents, any 10-square-kilometre area will have at least one polluted site. Once identified, we don't just ignore these sites. We carry out checks, and even do decontamination work.

Once you have identified a site, what do you do?

We have a whole strategy. Before acting, the main thing is to understand. To that end, we carry out studies. First, we piece together the story of how a substance came to be in the soil or the groundwater. Then we weigh up whether or not that substance will move. What mass of pollutants may have gone astray? Then we assess how serious it is, and whether any homes or water supplies are threatened.

It's a bit like going to the doctor's. We make a diagnosis and evaluate the situation. What happens once you've made

your diagnoses?

You're right. It's what we call a diagnostic phase. Understanding this phase will take time. In France, it's like CSI. We have environment detectives. I grab my hat and magnifying glass, and look for polluted sites. Techniques wise, there are three broad families of decontamination we can deploy if necessary. The first is something basic. In 50% of cases,

we take the polluted land and send it away to treatment or storage centres. It's effective but not virtuous. Pollution is moved from point A to point B, but nothing is solved. Another decontamination method consists in removing polluted soil, treating it on the spot, then putting it back. The final, more technical method, one we are making progress in, is treating soil pollution directly, on site. There are several processes. We can increase temperatures: heat the soil to degrade pollutants. But it consumes energy and can be expensive. We can also add products to the soil. Not dangerous products: there's no point adding one dangerous product to another. These are peroxide-type products,

iron-based solutions. We can also use the plants to fix or transfer pollution from soil to plant. But it takes time,

decades or even centuries. Bacteria can be used too.

You're absolutely right. Some bacteria can... Let's see. Some bacteria will break down pollutants.

How does that actually work? It's like the chemical diagnosis you described. We establish a microbiological diagnosis of our site. Then, in our polluted soils and waters, we seek out any bacteria capable of breaking down the pollutants.

For that we have a range of techniques. We can even examine bacterial DNA to gauge their potential, see how they can act. We take them into the laboratory and see whether they are capable of breaking down the targeted pollutants.

That's awesome! So, you breed bacteria? You turn weekend sportsmen into top-rank athletes.

That's right. Sadly, when they are in this soil, they don't always have what's required to complete the degradation.

It can be a long process. We study them closely, and give them whatever nutrients they need to actively degrade the pollutants. I'll give you an example with a site that was contaminated with hydrocarbons. Bacteria were present that could carry out the degradation. But they needed oxygen to break down the pollutants. Polluted Sites and Soils engineers injected oxygen into the soil to activate the bacteria. That can take time. But as things progress, with all the data accumulated on these mechanisms and how they work, we are finding more and more ways to clean up these soils.

That's interesting. Even though we're dealing with pollution, there are a lot of positives. We have grounds for optimism. Using super bacteria, can we prompt nature, even in its degraded state, to regenerate certain sites in France.

Absolutely.

So polluted sites are not a write-off. In many cases, polluted areas may even become an opportunity.

Absolutely. There's plenty to work on.

Thank you. Plenty to work on, then. With super bacteria, we have the supermen. Our Science Cabaret has some

great stuff, including super bacteria.

But we can't see them.

They're there, though. Thanks for that great presentation. Join Fred at the Science Bar. We'll clear that up...

Jennifer Hellal, Hubert Leprond, both from the BRGM, the Geological and Mining Research Bureau. Come and sit with us. Jennifer, you are a microbiologist. Careful, you're losing your truck! Hubert is in charge of the BRGM's "Polluted Sites, Soils and Sediments Unit". Without wishing to sound alarmist, I gather France has many polluted sites.

6,000, you say?

A little over 6,000.

Polluted by what?

Polluted by metals, hydrocarbons, solvents.

From old companies, industries, service stations?

Not necessarily large companies. There's no correlation between large companies and small-scale, local activities.

But there are a number of sites, as there are in other countries.

What's great is that we can use nature to repair human error through bacteria in the soil. Is this technique already operational? Is it growing, or is it still at the lab stage?

Both cases apply, as in the example I gave, where it's operational. We are continuing our lab research to find new bacteria able to degrade other pollutants.

Could it adapt to any type of polluted soil, or are some cases...?

Bacteria are helpful, but complex molecules are harder for them to deal with. But we can take action, then introduce bacteria or processes involving biological decontamination.

If I've understood correctly, these bacteria are already present in the soil and will clean it up, but you need to pep them up to make them top-rank athletes.

That's right.

Give them oxygen. Are these the only ones used? Or must bacteria be added to the soil?

Mostly it's about stimulating or encouraging bacteria already present on site. We make sure that they have all they need, all the required nutrients to carry out the degradation on site. Other bacteria are sometimes used, but that's less common.

Specific bacteria could be added to the soil? Sprinkle a bag of bacteria around the area?

In theory, yes. But introducing bacteria doesn't work so well. They are not there for a reason. It's easier to see what's already there and stimulate them - dope them almost - rather than thinking you can bring in new ones that will quickly acclimatize.

Does it take a long time to clean up soil? Obviously it depends on the area. Bacteria must work at the speed of nature.

They can work very fast. Maybe on the scale of a few months or a few years. It's relatively fast. In towns, we don't have much time. Given the desire is often to redevelop and integrate old wasteland rapidly, so work is required to ensure the schedule is met.

Sure, work is involved. Property developers always want to build fast.

Indeed.

That's what happens. But don't property developers usually want to clear the ground rather than let bacteria do their work?

It's something we need to think about in promoting these techniques. They cost less but take more time.

That should be your argument. It works.

Often it does.

I can imagine! Does it cost a lot less than the other techniques?

The more pollution we have, the more trucks are needed. It's proportional. Bacteria can be made to work

just by enlarging a pile of earth, so that can cost a lot less. It can make a significant difference.

But the time factor is important too. If we let bacteria work freely, it may take longer...

Than using a truck.

And excavating.

Christian, you just spoke about preserving nature. Once again we are turning to nature, to bacteria, to fix our mess.

In expeditions, I'll take a bag of bacteria to spread around and clean the ground I pollute.

Do you ever encounter polluted soil? Not in your world.

There is no miracle. When we venture into a territory, even if we're careful, we pollute a little. You modify a territory

the moment you enter it. I have a question. Is this technique being studied in other parts of the world? Could it be exported? In France, we have problems but some places have at least as many if not more. How can we work

with other countries?

There is cooperation. French companies go abroad. These biological and chemical techniques are also known

in many industrialized countries. The challenge is to be able to export this know-how and train people on the spot

so they can clean up their sites themselves.

Industrialized countries, emerging countries, many of which suffer exponential soil pollution. If the technique is cheaper, and the only cost is time... Time is money, some countries have more than others. Are we being pro-active about pollution in emerging countries?

Of course. In developing countries, in the East and in Africa, these techniques are working well. We mentioned temperature. The hotter it is, the more bacteria are active, so it can work in those countries.

OK. An interesting development path, and one with economic benefits.

"Science Cabaret": True or false - Social networks and earthquakes.

Transcription

We are going to play a true-or-false quiz with Samuel Auclair, an earthquake engineer at the BRGM: the Geological and Mining Research Bureau.Ready to play?

I think so.

It's a true-or-false quiz. We ask a question, the audience answers true or false. Later, we'll give you the answers.

Fred will play with us. If you know, don't say anything.

Can I give a few small clues?

Small clues? We'll see. No cheating.

I'll handle the microphone.

Let's begin. First question. When an earthquake strikes, the first alert is given by the emergency services. True or false?

True or false?

False.

True.

False.

False.

False.

I'd say false too.

Wait... I'm wondering... The question is: Earthquake alerts are given by the emergency services. I'd say yes. Why do you say false?

I'd say maybe... through TV broadcasts for instance. It's a broader scope.

That's one idea. Ma'am?

The people who monitor these events.

You mean the experts, who have the detection tools. Sir, what do you think?

I think it's false.

Why?

There are special agencies that monitor such things and check for earthquakes.

Shall we give the answer?

Listen...

Yes? People seem pretty informed.

So?

Samuel, true or false?

It's false. For earthquakes, neither emergency services nor scientists can give predictions. The earliest alert is given

by whoever feels it. It could be you. It might be firefighters, if they happen to be in the area. Citizens are in the front line for giving alerts.

OK. We'll say no more. Now for the next question. If a natural disaster strikes, the first reflex from many of us,

is to go on Twitter. True or false?

Carrying on the game...

False.

False.

True.

False.

False.

False.

It wouldn't be my first reflex.

True.

I'm unfamiliar with Twitter.

I wouldn't want to be next to you if there was an earthquake.

I said false.

Well, ma'am?

False. The evidence is that people pick up a phone and call their friends or family.

I'll come down to the front where we have a few experts.

For some, the answer will be yes, but it's better not to.

That's an opinion.

I'd say false.

You'd say false.

It's false.

It's false!

False.

Totally false.

What do you think, Fred?

I don't have an opinion, I'm neutral!

Meaning you don't know.

Yes, I do know.

Well, Samuel?

I know because I cheated. I already know a few answers.

So is it true or false?

True. For many people - not necessarily those present today - their first reflex in the event of an earthquake is to grab a phone and announce it.

It's a generational thing.

For sure. It's to do with people using Twitter. You realize the extent of the rapidity. You realize...

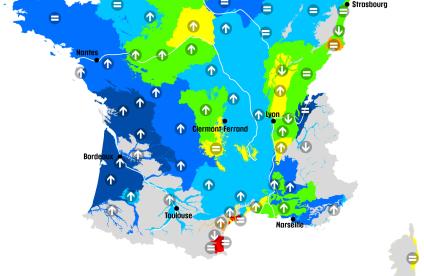

We have some images.

If I can get there... It shows that people... An earthquake took place in France a few years back, in Ubaye. Here we see the number of tweets per minute mentioning earthquakes. Before the earthquake, nothing. As the earthquake strikes, the number of tweets rockets. The first tweets arrive within a minute: about 50 seconds. 50 seconds to sense it, grab the phone, then if you're fast, have the time to write something and post it. And not use the time to make yourself safe. We're not saying it's virtuous behaviour. We've seen that people can put themselves at risk talking about it rather than taking measures.

People take selfies in front of a collapsing wall?

At least by saying: "It's moving!"

Can we just clarify? Did you show us a seismic curve?

No, it was the tweets curve.

It looks like it. Instinctively grabbing the phone, OK. But tweeting it?

Yes.

Via Twitter?

Yes, the time to send a message.

It's amazing. I just wanted to clarify that.

All the people who answered "false", what would you do? What would be your first reflex?

Ma'am?

The phone. Same as what happens aboard planes. People use their phone to inform friends.

To report a tremor or to find out if everyone is fine?

How long have we had tweets? How many years?

Good question.

Twitter has existed since 2006. In France, it was 2010 or 2011 before its use became widespread. A few months ago, in France, there were heavy rains in the Paris region, and a landslide on the RER. The RER stopped, the only information was on social networks. The early information came from pictures posted on the spot.

Here, it was an earthquake but does it apply to any type of disaster, this surge in tweets?

As soon as anything noticeable occurs, it's reported on Twitter. For incidents that affect several people simultaneously, we get a precise view. It may be a tsunami, or a fire, for example.

Next question. Messages sent from Twitter are meaningless. True or false?

Messages sent on Twitter are meaningless.

It depends.

Yes, it depends. Why true or false? It depends on the message!

There's one answer.

It depends.

Well!

I don't know.

It depends. I'm inclined to say false but it depends.

Same. Mostly false.

It depends.

One person said: "It depends." So, it depends!

I agree, it depends.

Yes, it depends.

Depends who sends it.

The answer?

To sum up, it's a fashion trend. So it depends. It depends, but it's often...

In the context of disasters.

It tends to be false. There's significant information in these messages. What you see on screen is a tweet that had...

Sorry. That wasn't what I was expecting. Some messages carry a lot of information. Within a few dozen minutes of

a big earthquake that ravaged Haiti, no outsiders knew what was going on. But tweets told us, described the scene,

what was happening on the spot. Destroyed facilities, many victims... It supplied information.

Are those tweets...? Before we have the next question... Are these tweets from citizens or from reporters, seismologists, experts on the spot describing what's happening?

As we said at the beginning, these people are there. Some witnesses are well-informed, better able to qualify the information, but often they're ordinary citizens. Sometimes, as was the case with the earthquake in France,

the information in the tweets is vague. "I hate these crazy earthquakes!" But each tweet says something. "Here, now, we felt an earthquake."

One final question concerning the importance of citizens. In France, sensors measure everything. Any earthquakes,

avalanches, rivers bursting their banks, we know instantly. True or false?

True or false? In France, sensors measure everything, everywhere. Seismic incidents, earthquakes, avalanches...

What do you think?

I don't know.

No idea.

No idea.

I have a few clues.

There are some, but not everywhere.

I think it's true.

I'd say false.

False? Samuel, who wins?

It's rather false. We wish we had them.

So we don't have them.

We'd like... to be able to constantly detect everything via sensors. We have more and more of them. But during your Sunday walks, you seldom come across a visible sensor that measures water levels, or earthquakes. Most of the time, we are the sensors: people all over the territory. That's the value of what's posted across social networks. In addition to sensors, you need feedback from people on the ground.

Where we don't have electronic sensors set up by experts, we have us. What I said earlier is false. It could be me raising the alarm.

It could be you, yes.

So all this information can be collected?

Yes, Twitter allows us to listen in. Those are the rules. Your friends can listen to you. For a few years now, we scientists have been listening in with a friendly ear. We're not being Big Brother, just collating and qualifying that information. For example, here's a picture that appeared on Twitter during the Seine flooding in January and February. For anyone seeking information about the impact of the event, it's significant and a great help in assessing water levels. The accompanying text often provides context. It has real value.

If I'm not mistaken, the added value of the citizen as a disaster sensor, raising the alarm, can be usefully applied

in your research.

At BRGM, we've started to create a platform called SURICATE-Nat in order to capture this data and systematically analyze it to qualify the event. It's a work in progress.

It allows you to establish trends in the information circulating on social networks about natural disasters.

Exactly. The idea is to be able to pass it on to the authorities.

Do I have time for a question?

Axel is waiting.

I hope he asks it.

Otherwise you can ask it at the end. We'll do that.

Samuel, you can join Axel to carry on this conversation.

We are with Léa Bello, Sébastien Carassou, Thaïs Hautbergue and Nihel Bekhti. Samuel Auclair, you are an earthquake engineer at the BRGM. We have a few minutes to outline this platform: SURICATE-Nat. Summarized in a few key words, Twitter-style, what is it?

It's a platform for the automatic analysis of information circulating on Twitter concerning natural disasters.

Is the objective first prevention, then event analysis? Or both?

Primarily the latter. We are analyzing events. People who post information are facing an event. In that moment,

it's the theme that matters, not the before or the after. We try to seize this moment of interest to help out with prevention.

How does the platform work? What does it allow you to see, and the general public to do?

It allows us to channel this information and analyze it. Subsequently it gives users an insight into what's happening

on the ground from what's being posted and talked about.

If an earthquake was starting now, in Paris, would it appear instantly?

Yes, within a minute. Peak activity indicates an earthquake: we can see what people are saying. After that, the algorithms get to work.

When was the platform launched?

It was first put on line in December 2017. It's very young. The idea is to continue working to improve analyses and diversify the types of hazards concerned. We focus on earthquakes, floods, and land movement. But with hurricanes and avalanches, there are many other things.

Which event since the launch has triggered the most tweets?

Since the launch, it was the floods in January and February 2018 around Paris. On the Seine and the Marne.

We can see here.

Tweets provided information: 70,000 tweets within a few weeks.

What do you do with the data collected? We can see the tweets. What do you do with them?

Each tweet is treated by algorithms to pinpoint exactly where it is in the territory and qualify the information therein. Is there any damage? Do people need help? Does it indicate water rising or receding? Those kinds of things. That's all automatic. It's what we're trying to do.

Sébastien Carassou, is following natural phenomena via social networks an attractive idea? It seems to me to be necessary in terms of public safety. But I have a question. How do we differentiate between: "I'm trapped in the wake

of a natural disaster" and "It's a disaster, I missed my train"?

We track particular keywords. We don't listen to anything and everything, we limit it to a scope. Markers, the way a tweet is written, often have an impact on what we read. For example, people who have just felt an earthquake tend to give shorter messages, with more capitals and punctuation. Algorithms can identify those markers. It's automatic learning.

If I tweet something on a real event or otherwise, will it automatically be analyzed? Does it scan all activity on Twitter?

That's the idea. It isn't tied to a particular community. A community of users doesn't apply to natural disasters.

It's of no interest...

No-one will sign up for that.

But the day you face one, our challenge will be to find your tweet and analyze it.

If a community created a fake earthquake, would you have an alert?

If the algorithm is unable to identify that they are fake, yes, it's possible. But you need to consider what you put in your tweets, because we'll see it!

Don't do it, it's a bad idea!