View of the Küre open-pit copper mine (Turkey, 2012).

© BRGM - Francis Cottard

Imagine an overgrown stretch of wasteland, what could be more ordinary? If only former mine sites could be just that. In reality, getting them back to an “ordinary” state can sometimes be challenging. Micro-organisms and plants can be used to manage risks from former mining operations: this “teamwork” is known as phytostabilisation.

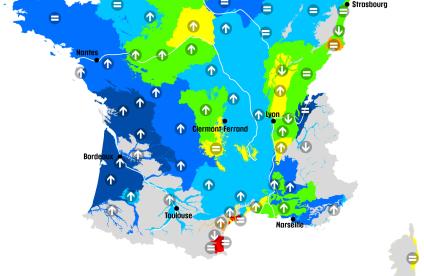

The process has great potential since it is an environmentally friendly and cost-effective technology, and France has more than 2,000 mineral waste storage sites needing treatment.

To understand pollution at these mining sites, we must go back and look at what the extraction process itself involved. To access the metals of interest, miners needed to extract large quantities of rock. Then, when the metal-rich vein was reached, the ore was ground to retain only the part with high levels of the sought metal. The waste was usually discarded and deposited next to the extraction site.

Why is this waste a potential pollution hazard?

Because it contains metals and other toxic substances, such as arsenic. The problem is that the waste, whether as stretches or heaps of sand, can release toxic dust into the environment. Often, the most profitable minerals are metallic sulphides, rich in sulphur and iron. When exposed to the air and the weather, these are dissolved by bacteria seeking energy from oxidation.

This can produce contaminated, acidic leachates, usually rich in iron and other metals. Scientists have discovered that micro-organisms and plants can help capture these pollutants.

An old silver mine in the Massif Central

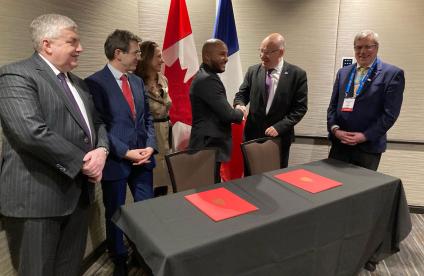

As part of the science project Phytoselect - supported by the Centre-Val de Loire region and coordinated by the Orléans Institute of Earth Sciences, with BRGM’s involvement - this phytostabilisation process has been thoroughly assessed.