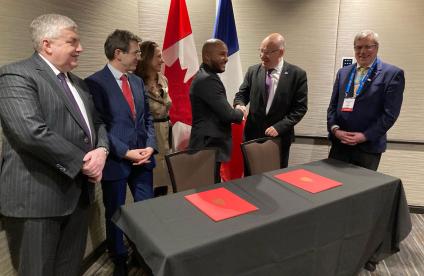

De-mining of the underground quarry at Vaucottes (Seine-Maritime, France, 2004).

© BRGM - Patrick Lebret

Once the army had been demobilised, these depots were less and less well guarded. Exposed to the elements and to day/night cycles, the munitions rusted, lost their distinctive marks and became unstable. Chemical munitions leaked. Inevitably, accidents happened, causing dismay and fear among the population, which was still painfully and laboriously trying to surmount the trauma of war in a context of material, agricultural and industrial reconstruction.

A colossal challenge in the aftermath of the war

The authorities soon realised that neutralizing this arsenal left over from the war was not only a necessity but also an emergency situation that had to be addressed. Never before in history had men needed to eradicate such quantities of incredibly diverse projectiles in such a short time. So where were they to start? It was necessary to prioritise actions by assigning a degree of urgency for interventions. It was first the French and American armies, that were still mobilised, which set about destroying the ammunition in 1919 by blowing it up in heaps and from a distance. Grenades were exploded in shell holes filled with water. Black American troops were mobilised for this dangerous work, as well as Indochinese workers (known as "Annamites") and prisoners of war.