In order to monitor groundwater tables, BRGM manages the national piezometric network, which comprises 1,650 boreholes. These enable it to determine in real time the quantitative state of the large aquifers that are exploited. Based on these data, BRGM publishes a groundwater status report to describe the state of the aquifers.

The state of aquifers

There are currently an estimated 100 billion m3, on average, of subsurface water resources in mainland France. About 30 billion m3 of water are abstracted each year for different needs.

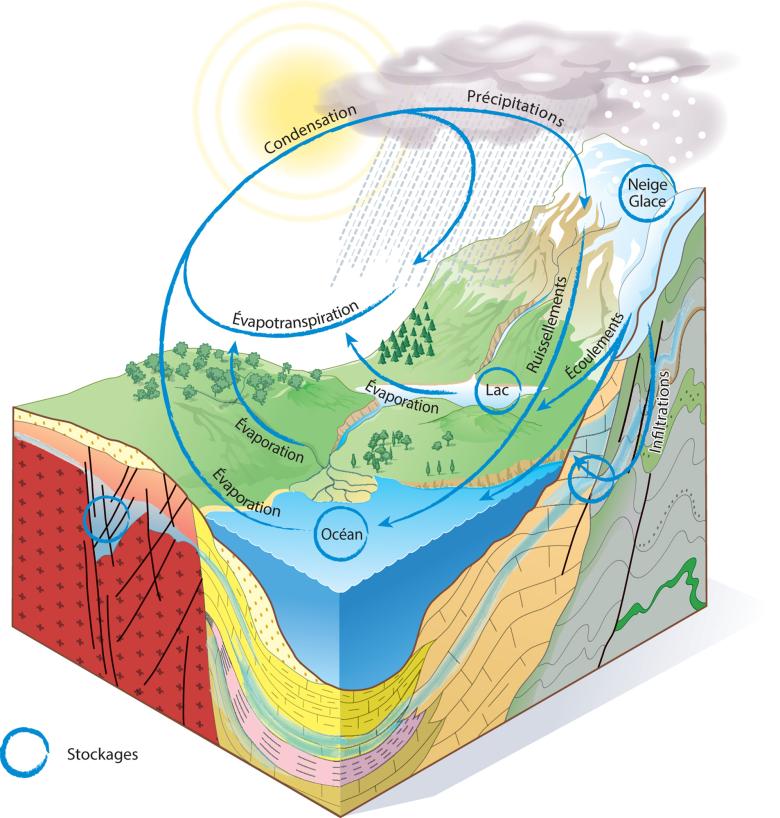

The aquifers are replenished by rain. They are mainly recharged in autumn and winter.

The water cycle and aquifer recharging

While some of the precipitation runs off, the subsoil becomes progressively wetter. Part of this water, more than 60% in France, is then redistributed to the atmosphere via evaporation from the soil and transpiration from plants. The remainder seeps deeper into the ground, contributing to the recharge of groundwater reservoirs and "aquifer recharge".

Groundwater: water contained in rocks

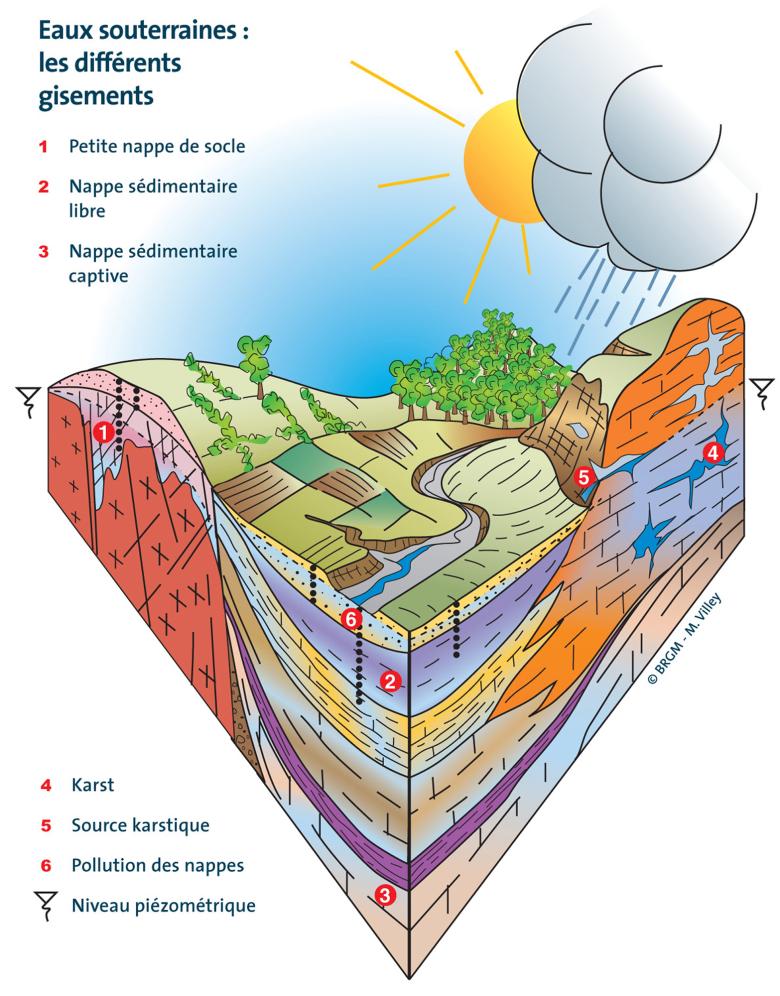

After the rain has infiltrated the ground we stand on, it circulates in the interstices and cracks of rocks, at varying speeds: this groundwater is called an aquifer (or phreatic aquifer). Aquifers are not, as we might think, underground lakes.

An aquifer is both a reservoir capable of storing more or less large volumes of water from infiltrated rainfall, and a conducting network allowing underground flows and the progressive emptying of the reservoir towards natural outlets (rivers or the sea).

Transcription

Water evaporates above the ocean and forms clouds. Water then hits the ground when it rains, and sometimes when it hails or snows. Part of this water flows on the ground. Another part infiltrates it. The water penetrates the top soil. In a few hours, it continues downwards, following spaces between the rock's grains. These empty spaces contain both air and water. This is called an unsaturated zone. When the water hits an impermeable layer, it can't go any further.

It accumulates and forms groundwater where the empty spaces between grains fill with water. This is the saturated zone. The water flows horizontally over this impermeable layer, moving a few metres per day towards the lowest point. As long as it rains, the groundwater fills up faster than it is emptied and its level rises. When it stops raining,

the level goes down. This is called groundwater drainage. From spring until autumn, even if it rains, evaporation from heat and plants will use up all the water that penetrates the top soil. This water won't go into the groundwater. At the lowest point, it continues to flow into the river. The groundwater level gradually lowers throughout summer and the river flow decreases. Water that enters a porous layer accumulates on the impermeable layer and forms groundwater

that flows horizontally. When the water goes underneath an impermeable clay formation, it will flow much more slowly, and its level cannot rise. It is blocked by the impermeable layer above it. In this confined groundwater, the water is under pressure. If we bore through the impermeable layer, water will come up the tube. If there is enough pressure,

it will even burst to the surface. This is called an artesian well. In the wild, there is often a superimposition of porous and impermeable layers. These pile up into a kind of tome as is the case in the Aquitaine basin.

Some definitions

Aquifers and groundwater

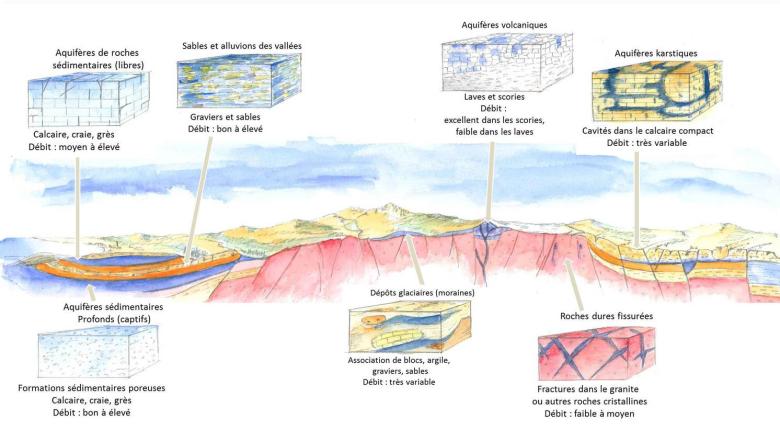

Geological formations that contain a significant volume of exploitable groundwater are called aquifers. An aquifer is a container, the groundwater is its content. Aquifers are not, as some might imagine, underground lakes: the water that circulates in them only occupies cavities in the rock (interstices, cracks, fractures).

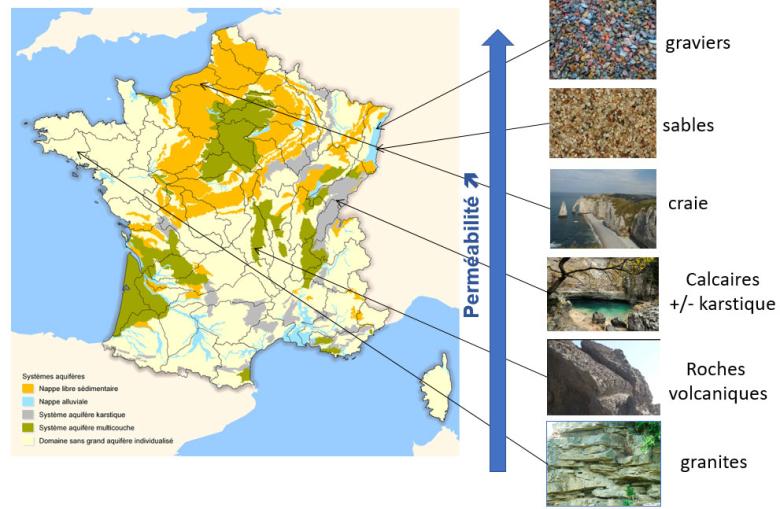

The main criterion for distinguishing between aquifers and non-aquifers is permeability, a parameter that quantifies the capacity of the geological formation to allow water to circulate. Recent sands (dunes), but also sands deposited by ancient Mesozoic and Cenozoic seas, are very porous and permeable. Limestone and sandstone formations are also very permeable. Such formations can be exploited by drilling wells that can deliver more than 100 m3/h. In some areas (Causses, Quercy, Jura, among others), significant dissolving of the limestone has given rise to karst formations, some of which contain actual underground rivers. Many springs, outlets of the karst massifs, are exploited for drinking water.

The rocks of the basement domains (granite, gneiss in particular) are characterised by cracks and more or less interconnected fractures. Abstraction rates are generally of the order of a few m3/h and rarely exceed 20 m3/h. This degree of permeability is lower than that of sedimentary rocks.

Free or confined aquifers

Among aquifers, a distinction is made between those in which the groundwater is free and those in which it is confined. In the first case, the free surface of the groundwater does not reach the upper level or roof of the aquifer. This roof may be the surface of the ground, in which case it is sometimes referred to as a phreatic aquifer. In the second case, the water table is trapped - captive - under an impermeable roof. It is then under pressure.

The captive aquifer of the green sands of the Paris Basin falls into the latter category. It is very well known, having been discovered, exploited and studied since the 19th century. It covers 75,000 km2 and contains 400 billion m3 of water according to geological estimates. The precious liquid flows at a rate of 2 metres per year. However, the so-called free aquifers are much more numerous: they account for 85% of the exploitable regional aquifers.

Two or more aquifers may be superimposed, separated by low-permeability layers. This is known as a multi-layer aquifer. There may be slow but significant exchanges between the different aquifer levels.

The winter recharge period: six decisive months

Groundwater levels vary throughout the year, from high levels in winter (when vegetation does not absorb rainwater) to low levels in summer (the classic discharge period).

The fate of rainfall varies greatly depending on the time of year and the condition of the ground surface on which it falls. Traditionally, the period of groundwater recharge is from early autumn (September-October) to early spring (March-April), a period during which vegetation is dormant (with low evapotranspiration) and precipitation is normally higher. If the winter is dry, groundwater recharge is very low.

From spring through summer, rising temperatures coupled with the regrowth of vegetation, and thus increased evapotranspiration, limit the infiltration of rainfall into aquifers. Between May and October, barring exceptional rainfall episodes, groundwater depletion usually continues and levels continue to fall until the autumn.

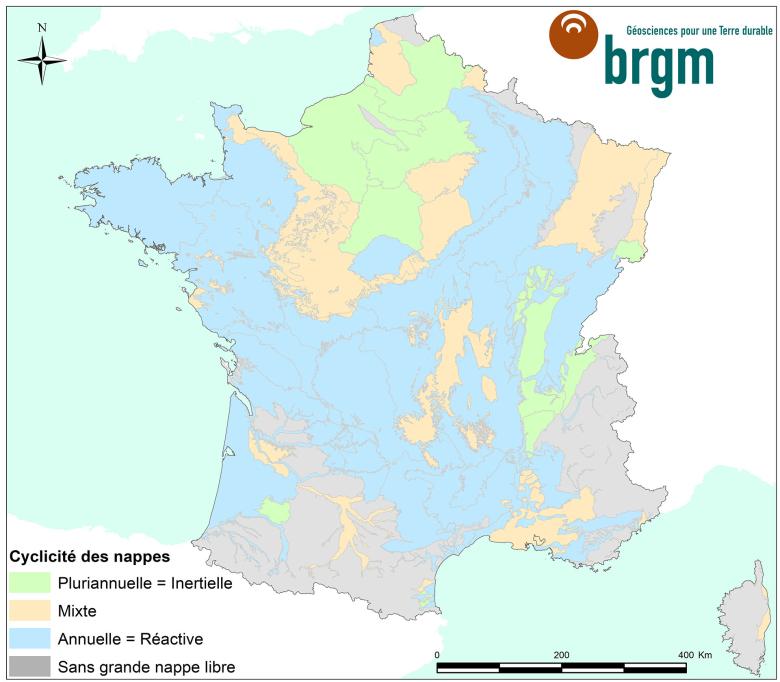

Cyclicity of groundwater recharge: inertial and reactive aquifers

Groundwater flows at different rates depending on the porosity (percentage of voids in the rock) and permeability (capacity to allow water to circulate, i.e. interconnectivity between these voids) of the aquifers. The larger and more interconnected the voids, the faster the water will flow.

A given volume of water can travel the same distance:

- in a few years in a porous environment: the water flows through the interstices in loose rock (sand, gravel) or consolidated rock (sandstone, chalk).

- in a few months in a fissured environment: the water is contained and circulates in the faults or fissures in the rock (crystalline rock - granite, schist - volcanic rock, non-karst limestone).

- and in a few days, or even a few hours, in karst environments: the water has dissolved the rock and widened the cracks, creating caverns (karst formations in Cretaceous and Jurassic limestone).

The impact of the quality of winter recharge differs according to the cyclicity of the aquifer, i.e., its reactivity to rainfall infiltration.

Inertial aquifers (chalk, tertiary formations and volcanic formations) have a multi-annual cyclicity. Their inertia, characterised by slow flows, allows them to maintain levels that are not very degraded at the end of a winter with a recharge deficit.

On the contrary, reactive aquifers with annual cyclicity (alluvial, Jurassic and Cretaceous limestone, Triassic sandstone and basement) are very sensitive to a deficit of effective rainfall.

How France monitors its groundwater resources

France has 6,500 aquifers, including 200 aquifers of regional importance (with surface areas ranging from 1,000 to 100,000 km2), hosted by various rock formations.

© BRGM

Determining subsurface reserves

Despite the diversity of its subsurface and the many unknowns, France has very rich databases containing knowledge of subsurface aquifers. They are now managed and developed by BRGM in cooperation with its partners. Approximately 6,500 aquifers of all sizes have been referenced in France, including 200 aquifers of regional scale (from 1,000 to 100,000 km2 in size).

In order to monitor the level of groundwater, as laid down in the water framework directive, BRGM manages the national piezometric network, which comprises 1,650 boreholes. The latter pierce deep into the subsurface and are used to determine in real time the quantitative state of the large exploited aquifers, since the piezometers (tubes for observing the level of the aquifers) are for the most part equipped with a particular technology (GRPS) which transmits the information remotely. Once or twice a year, technicians visit all the sites to manually check that the data sent by GRPS is consistent with the levels observed on site.

Monitoring groundwater quality

In addition, BRGM has made a considerable effort over the last 15 years to couple quantitative water analysis with qualitative analysis. The French Geological Survey thus includes in its measurement network:

- Tools for measuring groundwater temperature and electrical conductivity. The aim here is to better understand the link between the waters studied and the rise in sea level (with saline intrusions), as well as the exchanges with surface waters.

- Qualitative analysis tools for pollution risks. In France, companies, local authorities and water agencies have installed no less than 75,000 water-quality meters (distinct from piezometers that measure the level of groundwater) over the country. This enormous mass of information is collected by the ADES portal, developed and managed by BRGM. Its scientists use it to improve understanding of the transport and transformation of contaminants in the soil and then in the aquifers (nitrates, pesticides or emerging pollutants such as cosmetic residues or plant protection products). This work requires the development of new tools that will be able, for example, to "scan" all the pollutants in the water, and thus enable the mobilisation of resources in microbiology, hydrophysics, metrology, but also in analytics and experimentation. In particular, they will enable more accurate groundwater vulnerability maps to be made and the prediction of the impact of land use changes or protective measures on groundwater quality.

Earth sciences are essential for quantitative and qualitative water-management

BRGM dealt with the issue of water very early on. Since its creation, it has developed internationally recognised expertise in the quantitative and qualitative management of groundwater. BRGM relies on well-founded knowledge of the structure of the subsurface and the characterisation of hydrosystems (resource assessment, understanding of pollution transfers in groundwater).

Knowledge for management: the contribution of geoscience

The "hidden" character of groundwater and the great inertia of part of these reservoirs due to the slow flow are the two greatest assets of this resource, guaranteeing access to quality water that is preserved from surface pollution. But these advantages have a downside: the characterisation of the deposits, the understanding of their dynamics and their exploitation are more complex than for surface waters.

The contribution of geoscience disciplines is indispensable for the acquisition, standardisation and updating of data on geological aquifer formations and protective-envelopes of groundwater. As an expert in subsurface resources, BRGM contributes to the accurate assessment of groundwater resources and to the development of management tools for the various French water stakeholders, such as the water agencies.

FAQ - Frequently asked questions about drought and groundwater

Groundwater resources and databases in France

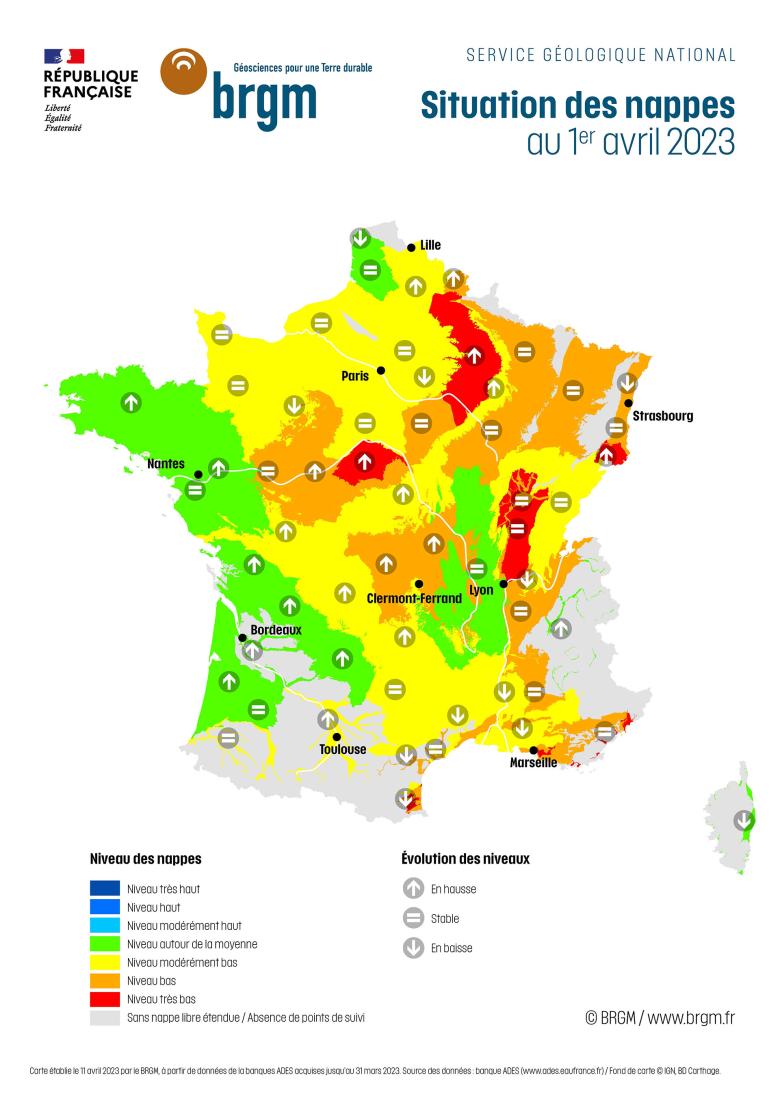

BRGM's groundwater status report: a statistical vision over time

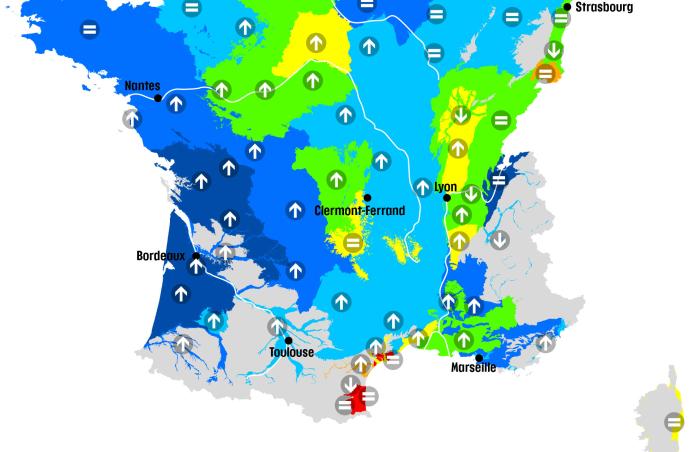

BRGM, the French geological service, publishes its groundwater status report 10 times a year (once a month except for February and December); it provides an update on the quantitative status of aquifers. This status report compares the current month’s figures with those of the same months in the entire record, i.e., at least 15 years of data.

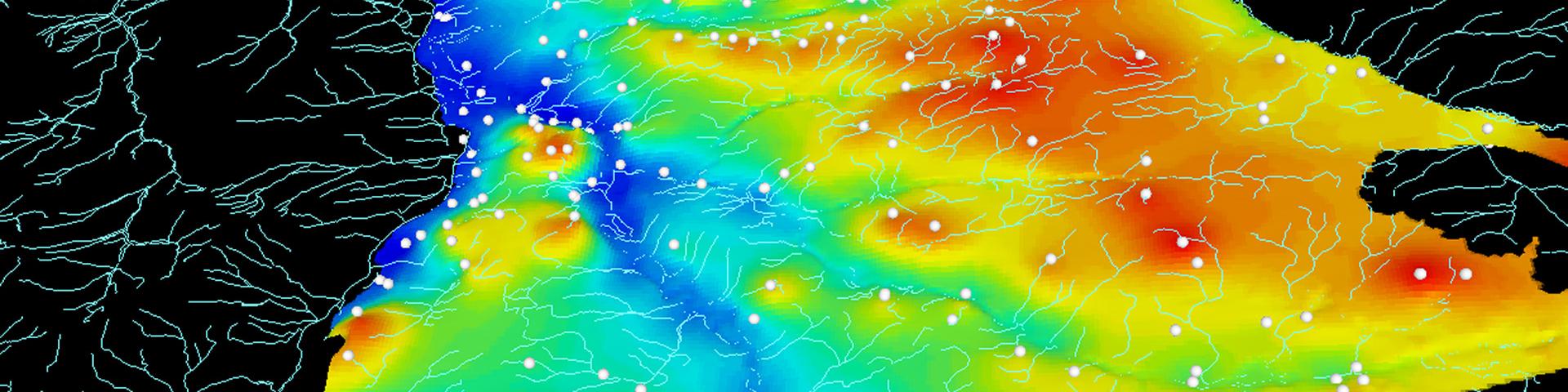

Based on the levels provided by the piezometers of the national monitoring network, BRGM establishes level indicators to facilitate data interpretation. When a piezometer borehole has yielded at least 15 years of data, it is considered to be capable of establishing monthly averages and a standard deviation. A given aquifer will thus be considered to be high or low compared to the average for the same month over at least 15 years. This average itself evolves over time as it adds the levels of the previous year. The oldest records of the national piezometric network date back more than 100 years.

Since 2017, the calculation used is based on the standardised piezometric indicator. It is consistent with the standardised precipitation indicator (IPS - indicateur standardisé des précipitations) developed by Météo-France, which facilitates comparison of the state of aquifers with climate episodes.

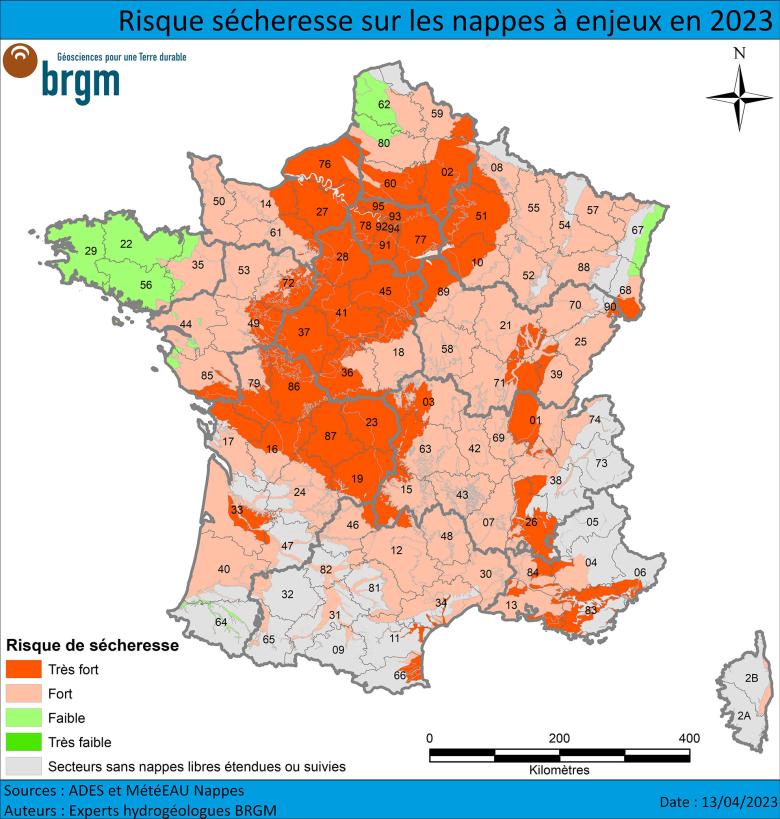

Seasonal forecasts and drought risk map

Each month, Météo-France produces a report of major trends for the next three months. It is not a weather forecast to provide information on the expected weather in France on a given day, but to identify likelihood trends at the European level. These forecasts are used by BRGM to produce a projection of the state of aquifers, which is included in the monthly report on their actual state.

In addition, BRGM has been producing a map of summer seasonal forecasts on the condition of aquifers since 2021. The drought risk map is based on the initial state of the aquifers after the winter recharge period, on seasonal forecasts from Météo-France, on seasonal forecasts from hydro-geological models and also on the expertise of BRGM regional hydro-geologists.

Hydrological status report

The national hydrological status report consists of a set of maps with corresponding comments that show the monthly evolution of water resources. It describes the quantitative situation of aquatic environments (effective rainfall, river discharge, groundwater table levels, reservoir/dam filling status) and provides summary information on Prefectural Orders issued to limit water use during the low-flow period.

BRGM contributes to the groundwater section of the French Hydrological Status Report.

ADES: the French portal for access to data on groundwater in France

BRGM has set up a database and a corresponding website, which is accessible to all water stakeholders but also to the general public: ADES. It brings together quantitative and qualitative data on groundwater in mainland France and the overseas departments, obtained from thousands of French piezometric boreholes and tens of thousands of wells used to monitor groundwater quality. ADES is a major communication and management tool for groundwater monitoring, which provides easily accessible data.

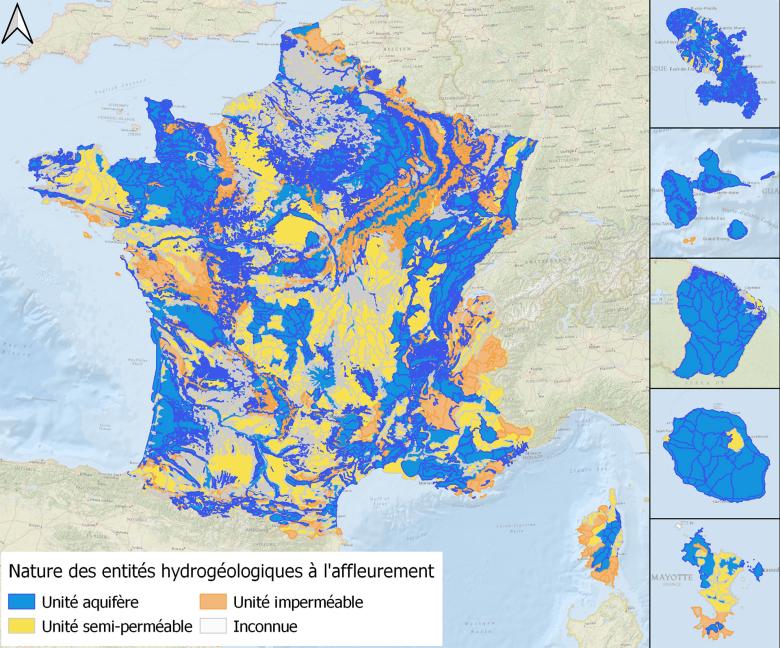

Map of outcropping hydrogeological entities, classified by type, in Version 3 of BDLISA, the French hydrogeological database.

© BRGM

BDLISA, the French hydro-geological repository

To facilitate access to knowledge of the state of aquifers, and to enable better management of the resource by government departments and local authorities, BRGM has conducted a vast project over the last 10 years to unify the data in a constantly evolving repository: the Aquifer Systems Limits Database (BDLISA - Base de Données des Limites des Systèmes Aquifères). This is the cartographic repository of the water information system. It provides a spatial overview of the major groundwater bodies in France. Its use requires training which BRGM provides at its headquarters in Orléans.

The BDLISA repository can be used to define the aquifers to be reserved for drinking water supply in the event of a water shortage, to identify the causes of a flood by revealing the possible role of groundwater (overflow), to determine the risk of marine intrusion into the groundwater in coastal areas, or to study the technical and economic feasibility of an artificial recharge solution.

MétéEAU Nappes, a tool for the real-time monitoring and forecasting of aquifer levels

BRGM has developed the MétéEAU Nappes website, which displays real-time data of measurements carried out by the national piezometric network, for various monitoring points linked to the global hydrological model.

These data are displayed as maps and dynamic graphs based on modelling and forecasting of water table levels during low- and high-water periods. Meteorological, hydrological and piezometric data from 13 representative sites in mainland France are published on-line in real time. Combined with the general models used (Gardenia and Tempo ©BRGM), these data are used to forecast aquifer levels. The forecasts (which cover 6 months) are compared with piezometric thresholds (for example: drought thresholds taken from Prefectural decrees concerning restrictions on water use).

MétéEAU Nappes provides a whole range of services that enable users to monitor the current and future behaviour of aquifers in France. It is a practical decision-support tool for managing water resources in sensitive areas (management of low flow in rivers, risk of flooding due to rising water tables, etc.).

Water evaporates above the ocean and forms clouds. Water then hits the ground when it rains, and sometimes when it hails or snows. Part of this water flows on the ground. Another part infiltrates it.